#28 Visa - The Giant that Never Sleeps

Understanding Visa's business model and insights into how it can add value in Africa

Hi all - This is the 28th edition of Frontier Fintech. A big thanks to my regular readers and subscribers. To those who are yet to subscribe, hit the subscribe button below and share with your colleagues and friends. 🚀

When I started my career in banking, I had it in for every part of the banking ecosystem. I thought that core banking vendors were too expensive and should all come crumbling down. I was of the view that Visa charged merchants excessive fees and that they too should be disrupted and I was of the view that SWIFT was archaic and completely useless. In retrospect, I don’t regret a thing, reimagining things is a useful exercise as only then do you learn, sometimes painfully about what it is you’re actually reimagining. Now I’m much less revolutionary and I have a deeper respect for some of these participants within the global financial system. The key has been to break them down into their constituent parts and appreciate the value in what exactly they do. Readers of this newsletter will appreciate my views on core banking systems. They do an amazing job of keeping financial records which are the lifeblood of financial services.

In the same vein, I have come to appreciate the card networks both Visa and Mastercard and particularly Visa which has a global market share of payments volume of approximately 60%. The appreciation has stemmed from the fact that Visa and its growing capabilities loom large across Fintech. Whenever you encounter a potential use case in a Fintech app, Visa is never that far away. It’s a testament to its enduring value proposition as a provider of global payments capabilities.

In today’s newsletter, I will cover the origins of Visa, its current capabilities and business model and review some of the ways I think Visa can embed itself deeper into the Fintech ecosystem in Africa and maybe even globally. Visa offers many lessons to banks and governments keen on setting up multi-sided payment networks. Though the lessons may be learned, few if ever will be implemented.

A Crazy Experiment in Fresno, California

Back in the 1950s, the retail payments experience particularly at a merchant level was fragmented. Some shops maintained proprietary credit systems that are almost similar to what a number of African kiosks offer. These systems were executed through charge cards that were issued by those specific shops. The card would maintain details of your limit and transactions would be recorded on a ledger. At the end of the month, the shop would send each of their customers invoices showing how much they owed the shop. You can imagine then that given each merchant maintained a proprietary card system, most people’s wallets bulged with multiple charge cards.

On the other hand, banks offered personal loans to individuals, but converting this to cash to then spend at the merchants was quite an ordeal. Definitely a better solution was required. J.P. Williams, then a banker at Bank of America thought that there could be a better solution to all this. After much haggling, he convinced his bosses at Bank of America of the idea of a credit card. The idea was that Bank of America could pre-approve a specific limit on a card and then issue this card to its customers. Merchants would be guaranteed settlement but at a 6% charge and customers could spend freely so long as they spent within their card limit. At the end of each month, Bank of America could send a statement to each customer for settlement. The cards would be called BankAmericard.

Bank of America then needed an area where both merchants and shoppers were Bank of America customers. Enter Fresno, a small town of around 112 square kilometres in the San Joaquin valley of California. Bank of America then “dropped” over 60,000 cards to all the residents of Fresno. Residents used them and merchants accepted them. Buoyed by this, Bank of America then issued the cards in Modesto, Bakersfield, San Francisco, Sacramento and then Los Angeles. It is worth noting that the regulations at the time didn’t allow banks to provide their services across the country. Bank of America was thus limited to the state of California. (As a side note, I love the story of Bank of America and its founder Amadeo Peter Giannini - which is well detailed in the book “The Innovation Stack by Jim Shelvey). Within 13 months of the initial drop, some 2 million cards had been issued and over 20,000 merchants were accepting these payments.

This card dropping experiment ended badly for J.P Williams, in the two years since starting the drop, Bank of America had lost over US$ 8.8 million and had a delinquency rate of over 22%. Nonetheless, Mr. Williams had proven something useful. The key learnings were that;

With better credit collection and management, the cards would be profitable for issuers;

Merchants were willing to accept a 6% charge as a convenience fee;

The latter could be summarised by a comment from Joe Nocera’s book “A Piece of the Action”

Fresno’s shop owners knew for a fact that, on the day the program began, some 60,000 people would be holding BankAmericards. That was a powerful number, and it had its intended effect. Merchants began to sign on. Not the big merchants, like Sears, which had its own proprietary credit card and saw the bank’s entry into the credit card business as a form of poaching. Rather, it was the smaller merchants who first came around. Larkin remembers visiting a drug store in Bakersfield, hoping to persuade its owner to accept BankAmericard. “When I explained the concept of our credit card,” he says, “the man almost knelt down and kissed my feet. ‘You’ll be the savior of my business,’ he said. We went into his back office,” Larkin continues. “He had three girls working on Burroughs bookkeeping machines, each handling 1,000 to 1,500 accounts. I looked at the size of the accounts: $4.58. $12.82. And he was sending out monthly bills on these accounts. Then the customers paid him maybe three or four months later. Think of what this man was spending on postage, labor, envelopes, stationery! His accounts receivables were dragging him under.”

A store owner who accepted the credit card was, in effect, handing his back office headaches over to the Bank of America. The bank would guarantee him payment — within days instead of months — and would take over the role of collecting from the customers. As for the bank, in addition to taking its 6 percent cut, the card was a way to get its hooks into businessmen who were not yet Bank of America customers. - Source: Stratechery

On the back of this, Bank of America licensed its credit card system to banks across the country. This was due to the fact that they had no way of assessing the creditworthiness of customers outside its franchise as well as the fact that it would be impossible to have all merchants open accounts at Bank of America. In this system, Bank of America offered accounting software and marketing support for a fee of US$ 25,000 per license. Nonetheless, it did not and could not offer centralised clearing. A merchant’s bank had to seek settlement directly from the issuer's bank. Clearly this would present a reconciliation nightmare and for sure suspense ledgers ballooned. It was a back-office headache.

Enter Dee Hock, a man considered to be the ultimate OG of Fintech, a visionary who only got his due recognition much later in life. Dee Hock was a manager at the National Bank of Commerce. Given that he had experience working at a licensee bank of the BankAmericard, he had a first hand view of the issues that bedevilled the system. His solution was innovative yet simple. It centred on two core concepts;

The nature of the organisation;

The nature of payments settlements;

The Nature of the organisation

Dee Hock believed that to work better, the system had to have participatory and decentralised ownership. Hock believed that all 3,000 members of the then BankAmericard system needed to revoke their licenses and form a new organisation that would own the overall system. This would engender trust which was critical for a payment system. At the time, it must be noted that given that cardholder banks needed to settle with merchant banks, failed or delayed payments had become a regular occurrence. An organisation owned and managed by the participating banks would improve governance and drive trust.

The Nature of Payments

Another insight that tied into the nature of the organisation centred around the nature of payments. Copying from Marc Rubinstein’s newsletter, Dee Hock noted that the credit card system should extend beyond credit cards. The core principles were;

The first primary function of the card was to identify buyer to seller and seller to buyer.

The second primary function was as guarantor of the value data.

The third primary function was origination and transfer of value data.

The insight, revolutionary at the time, yet not quite fully understood even now was that the whole payment system was a data transfer mechanism. It’s important to note that physical cards are a relic of the existing technology at the time. In principle, they are a representation of an identity within the Visa network. As payments become digital, cards will be a misnomer and the more appropriate term could be Visa “addresses”. Additionally, each swipe initiates an exchange of information and thus in theory any type of information could be exchanged. In the words of Dee Hock;

“…It was a revelation then. We were not in the credit card business. Credit card was a misnomer based on banking jargon. The card was no more than a device bearing symbols for the exchange of monetary value. That it took the form of a piece of plastic was nothing but an accident of time and circumstance. We were really in the business of the exchange of monetary value.”

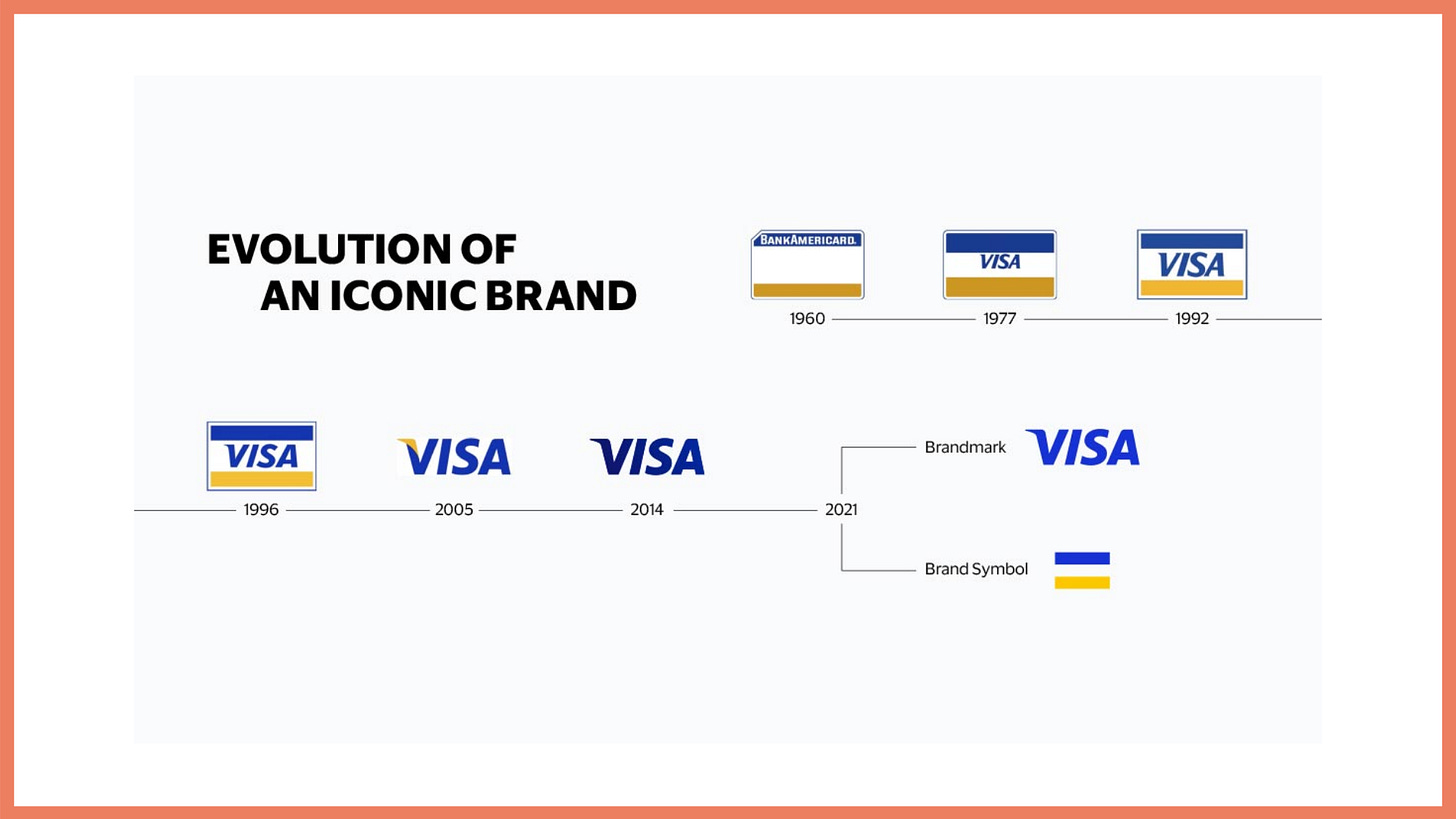

By 1970, Dee Hock was the CEO of this new organisation which took on the name “Visa”. He managed to put the constituent ingredients together so as to form a trusted and global payments system. Trust was driven further by assigning the “Visa” logo on all cards whilst running an aggressive consumer marketing campaign which had the tagline “think of it as money”. Visa continues to spend over US$ 1 billion a year on marketing.

It’s worth keeping this in mind when thinking about Visa. In 2007, Visa listed its shares and became a public company with most of the constituent bank shareholders divesting their shares.

Visa - A Multi-sided Global Platform

So how does Visa work, it’s useful to think of Visa as a global data exchange network that drives payments. The core business is centred around enabling C2B payments through its system of issuers and acquirers. For those who are keen to understand how Visa Payments work, an older post on global payments gives a good background.

For the purposes of this newsletter, what matters is to understand the crux of the business model. Visa is a multi-sided platform that connects on one side cardholders or consumers and on the other side merchants or recipients of payments. Visa has grown to multiple other verticals but this is the core of their business. Like with all platforms, there is a money making leg of the platform and a subsidised part of the platform. In the case of Facebook, Facebook users don’t pay to use Facebook. Marketers on the other hand, pay to reach Facebook users. In this multi-sided platform, users are subsidised by advertisers. In the case of Visa, merchants pay for the platform with banks and consumers enjoying the positive economics of the Visa Platform. Banks earn from interchange fees which accrue to card issuers on each transaction performed on the Visa Network. Merchants pay for this interchange which is often a percentage of the sales. Customers benefit from both not having to pay transaction fees and in many cases, cash back from their issuer banks particularly on credit card transactions.

As of FY 2020, Visa generated US$ 21.8 billion of net revenues on a total transaction volume of US$ 11.3 trillion. Globally, the US accounted for over 46% of total payments volume and roughly 50% of total revenues. Asia Pacific and Europe each accounted for roughly 19% of total payments volumes. There was an almost 50-50 split between credit card and debit card volumes globally. Over 3.5 billion Visa branded cards have been issued globally with over 70 million merchants accepting Visa Cards. The number of Merchants excludes merchants that accept payments on platforms such as Stripe, Paypal and Adyen. If these were included, then the number of Merchants is much higher. Visa is as ubiquitous as Coca Cola being present in over 174 countries.

The diagram shows the revenue profile of Visa.

Source:

Visa has a total market cap of US$ 513 billion (as of 8th August) and is worth more than all the original constituent banks. The core product in Visa is the VisaNet processing network. Nonetheless there are a number of adjacent verticals which have been showing impressive growth. The diagram below best captures the overall Visa value proposition.

Source: Visa 2020 Annual Report

Visa has a few core elements which in my view drives its value and enduring competitive advantage.

Customers - Visa has an over 60% market share in terms of total cards issued compared to the likes of Mastercard, JCB, Diners Club and American Express. All of its marketing efforts are targeted towards the customers knowing fully well that as customers grow, merchants have little choice but to accept Visa payments albeit begrudgingly. This is worth considering especially as Open Banking payments are being marketed as cheaper given that they will reduce the costs to merchants. The issue of course is that this doesn’t impact the consumer at all. In fact, a shift to open banking could reduce the cash backs on offer from card based payments. This is the magic of a multi-sided network, once embedded, it’s almost impossible to dislodge. You have to offer a 10x better value proposition to all sides of the platform.

Trust and Reliability - Visa’s core processing network VisaNet processes towards 1,700 transactions per second and has a reputation for security and reliability. The issue when you’re competing with cash is that you have to be as reliable as cash. A 2019 analysis by Growth Street Capital calculated that UK Open Banking uptime was only 83% thus hobbling growth. In India, UPI which has taken off reports uptime of 99.9%. From the Annual Report;

Trust is at the core of Visa. Through an evolving and multilayered approach, Visa strives to expect the unexpected, constantly monitoring our network and sharing intelligence with our partners. Our multi-prong security strategy is based on empowering consumers and clients through tools, resources and controls to make more informed risk decisions. To provide these tools, we invest in intelligence and technologies that improve fraud and authorization performance. In fiscal year 2020, Visa Advanced Authorization risk scored 141 billion Visaprocessed transactions – each transaction across more than 500 risk factors in about one millisecond. In the last year, Visa’s artificial intelligence (AI)-powered risk scoring engine helped financial institutions prevent nearly $25 billion in fraud. - Visa Annual Report

Simplicity and Platform Approach - In this podcast on Business Breakdowns, Alex Rampell a GP at Andreesen Horowitz explains how Visa barely innovates on its core product given that it’s just a payments rail. The core value of the Visa network to all parties is that it works and is reliable. Nonetheless, in addition to simplicity, the beauty of Visa is that it allows people to innovate on top of its offering. Almost all big Fintechs have partnered with Visa either to issue cards or acquire merchants. This is a key principle. One of the issues with African mobile money platforms is that they somehow stifle innovation. With all of them, there’s a “kill-zone”, once your volumes approach a certain level, they somehow conspire to launch a similar capability directly to increase their revenues and wipe you out. The simplicity of the Visa network builds trusts from all the companies that innovate on top of Visa.

Venture Capabilities - Visa has a 50% net margin on revenues north of US$ 20 billion with cash balances of roughly US$ 17 billion. This coupled with its ubiquity and global presence powers an acquisition culture that is the envy of many global VCs. Some of its recent acquisitions include their recent acquisition of Tink for US$ 2.15 billion, an acquisition of CurrencyCloud for US$ 700 million and a 2019 acquisition of Earthport for US$ 257 million. All these acquisitions fit into their global vision to be a leader in global payments. It is slowly marching towards sitting at the centre of global payments in whichever form they may take from Crypto to Account to Account payments.

Future African Use Cases

I started this newsletter by stating how Visa looms large and you can’t seem to escape it. I see value in the following propositions;

Cross-Border Payments - One can envision Visa particularly through its Visa Direct product enabling Cross Border payments in Africa and powering all types of payments including SMB payments. This is premised on growing financial inclusion and increasing smartphone penetration given that it would be cheaper to issue virtual cards as opposed to physical cards in many instances. As mobile money platforms switch more of their customer base to smartphones, I see them enabling virtual card issuance. I’ve noted in my newsletters before that mobile money would increase in utility if customers were able to travel with their wallets rather than just making payments. Visa can empower this. One likely approach would be to acquire a firm such as MFS Africa.

Open Banking in Africa - Visa’s recent acquisition of Tink and their previously failed acquisition of Plaid lays bare their Open Banking ambitions. In Africa, a continent wide open banking proposition would be particularly useful. For instance, Visa can drive more trust in their payment platform by enabling credit verification i.e. confirming to the sender that the recipient has indeed received the funds. One likely approach is to invest at early stage level in African open banking companies such as Mono, Pngme and Okra whilst waiting to see which one scales. At maturity, this can then transform into a full acquisition;

BNPL Cards - I did an article on the global Buy Now Pay Later space a couple of weeks back. My view was that BNPL was a feature and a number of BNPL players will either convert into banks or be acquired by other Fintechs. During the Week, Square announced a US$ 29 billion acquisition of Afterpay. Nonetheless, I see Visa enabling BNPL capabilities on their cards and launch BNPL cards in addition to their current credit, debit and prepaid offerings. This would be particularly useful for trade particularly if open banking and mobile money data is combined to drive improved credit scoring in the continent. You could see for instance traders buying goods using BNPL and paying off in instalments.

There are numerous capabilities that could emerge once you think of Visa as a data exchange network. Visa has been around for over 60 years and using the Lindy approach then it’s likely that they will be around for the next 60. It will be interesting to watch but one thing is for sure, Visa will continue to play an outsized role in the global payments ecosystem.

As always thanks for reading and drop the comments below and let’s drive this conversation.

If you want a more detailed conversation on the above, kindly get in touch on samora.kariuki@gmail.com;