Perspectives on Open Banking - Global Insights

Analysing the different models that Open Banking can take in Africa

Introduction;

Open Banking has been gaining traction across the world as a new paradigm in financial services. In a data driven economy with modern technology radically altering the distribution of financial services, open banking can create significant opportunities within the Fintech space. My whole angle this week is to look at the different implementations of Open Banking and see what lessons can be learned for most African countries trying to implement the same.

First, a primer on open banking. My first article covered the potential for Open Banking in Kenya. In essence, open banking is premised on the fact that a bank customer owns his data and should be able to give access to this data securely to another institution of his choice. The implementation of open banking is thus centred on giving access to your banking data to third parties through standard, secure APIs. This is augmented in most cases by giving third parties the ability to initiate payments from your bank account. Thus the two core areas of open banking are Access Initiation and Payments Initiation, though the two are not mutually exclusive. You can have access initiation without payments initiation and vice versa.

The drivers for the global open banking movement particularly in the UK which is considered a pioneer market in open banking, were largely based upon the competitive nature of banking markets in most modern economies. Across Europe and the Western world in general, the banking sector had over many years consolidated into big-four type markets. In the UK, the big four include Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds Banking Group and Natwest. In Australia, you have the National Australia Bank (NAB), Commonwealth Bank, ANZ Bank and Westpac.

The issue with big four dynamics which are essentially oligopolies is that banks don’t have to compete and with time customer value propositions deteriorate. It is with this in mind that the UK Competition and Markets Authority released a report in 2016 which paved the way for open banking implementation by mandating the sharing of customer data with Fintechs as a way of improving consumer choice and value.

These same dynamics i.e. a regulator led mandating of open banking have also been present in Australia, Hong Kong, European Union and Nigeria.

Different Approaches to Open Banking

There seem to be three main approaches to open banking - in this case where open banking is defined as the ability to share banking data with third parties through secure APIs. With the additional functionality of executing payments. So both access and payments initiation. The three are;

Regulator Led;

Market Led;

Hybrid Models

Regulator Led

In the regulator led model - open banking implementation is led by a regulator. In the case of the UK, the initial push was the Competition and Markets Authority and later the Open Banking Implementation Entity was formed to drive the implementation. Similar regulator led initiatives have been implemented in Europe via PSD2, Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore and Nigeria.

The overall framework includes banks, fintechs and accredited data providers i.e. entities who connect to the bank APIs and centralise them for Fintechs to consume.

Apart from Nigeria, the regulator driven model seems to be useful where the following elements are in place;

Mature banking markets characterised by financial inclusion ratios of above 90%

Presence of Big 4 market dynamics i.e. 4 large players who control the bulk of the market. In the UK for instance, the C4 ratio in the retail banking sector is 65%. In Australia the C4 ratio is over 80%;

A lack of global tech giants domiciled in these markets - unlike US and China, there are very few software giant companies from Europe, Australia and UK with a consumer focus such as Alibaba, Tencent and Facebook;

Bank accounts are the primary stores of value;

Nigeria has had a regulator led initiative nonetheless doesn’t share most of the above characteristics. There is still low financial inclusion with only 39% of adults having an account in a financial institution. Contrast this to 94% financial inclusion in Australia. The Asian models in Singapore and Hong Kong seem to be driven by high financial inclusion as well as proactive regulators.

Market Led

Market Led initiatives have occurred organically without any regulator mandate. Market Led initiatives have occurred in China, USA and New Zealand although the New Zealand example is arguably a mixed Hybrid. In 2018, six organisations formed Payments NZ which conducted an open API pilot. The six organisations were ASB, BNZ, Datacom, Paymark, Trade Me and Westpac – a mix of banks and third parties. They built and tested account information and payment initiation models. The Central Bank backed this project once the pilot was successful and later rolled out in 2019.

In China and the USA, the roll out of open banking has been purely market driven. In the US, Plaid has led the implementation of access initiation through its API. Now it has connected to over 11,000 institutions across the USA, Canada and Europe. The beneficiary of this move has been payment apps such as Venmo and CashApp which are now able to offer a more holistic financial experience to their clients. Additionally, it helps clients save on interchange by enabling ACH through the banking partners.

The Chinese experience has largely focused on banks sharing their APIs with super-apps such as Wechat and Alibaba. Only later in late 2019 did the regulator propose regulations to oversee the sharing of Open APIs.

The market led model is largely driven in my view by the following factors;

A disjointed financial ecosystem - in the USA for instance there are thousands of community banks, large national banks, fintechs such as Cash App and Venmo and numerous other players in the financial ecosystem. In China, there are also a multitude of players. Contrast this with the UK and Europe where banks have managed to cover most demographics. For instance, the top 15 banks in the USA have a market share of 56% whereas the top 4 banks in Australia have a market share of 80%;

The presence of tech giants such as Ant Group, Tencent, Google, Paypal and Amazon. I think the presence of a disjointed financial ecosystem coupled with massive tech players presents a number of attack points in the financial space. We have already seen this in China where Tencent launched WeBank to focus on the unbanked. In America, Square launched CashApp to take advantage of the same opportunities. What this does is that it incentivises the banks to cooperate because the alternative is having the tech giants take all your lunch;

Augmenting the two points above is a point about market power. In the UK for instance, the largest company by market cap in the FTSE is Royal Dutch Shell with a market cap of roughly US$ 150 billion. The largest bank is HSBC with a market cap of US$ 118.5 million. The largest company is thus 1.27x bigger than the largest bank and will likely never be a competitor to HSBC. Contrast this to China and the USA. In China, Tencent has a market cap of US$ 806 billion whilst the largest bank ICBC has a market cap of US$ 288.84 billion i.e. the largest company is 2.8x bigger. In the US, the largest company is Apple with a market share of US$ 2.1 trillion whilst the largest bank is JP Morgan with a market share of US$ 469 billion thus 4.5x bigger. In both China and US, the largest companies are already actively participating in the financial industry - the incentive is thus to collaborate and play ball;

Hybrid Model

The best Hybrid Model is India’s model. India is a very interesting example since it shows how the government can actively participate to build modern world class digital infrastructure. India does not have a de jure open banking system i.e. the regulator has not mandated open banking nonetheless both Access and Payments Initiation are fully at play. The core elements of what has come to be called India Stack are the following;

Aadhar - Presenceless Layer - The Aadhar system is the most successful implementation of a biometric identity system that has ever been rolled out. I say this due to the sheer complexity of implementing such a system in India as opposed to say Estonia. Aadhar is a biometric identity register that is API based enabling interoperability whilst maintaining data privacy. In India, the digital onboarding is thus solved since the RBI enabled banks to use Aadhar data as eKYC;

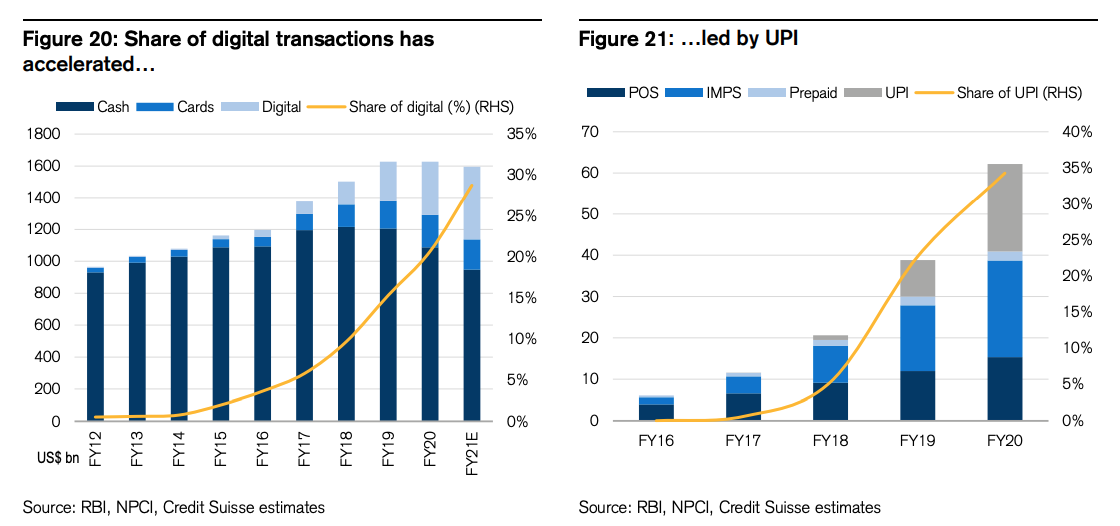

Unified Payments Interface UPI - Payments Layer - The UPI is a universal low value, API driven payments layer within the financial system that enables interoperability in payments i.e. payments can terminate in both digital wallets or bank accounts or any other stored value account. The interesting thing about the UPI for me is the conception story. The RBI created the National Payments Corporation of India (NCPI) in 2007 through the Payments and Settlements System Act. The idea was to create an independent non-government and not for profit institution that was to build out payments infrastructure in India. Later, the management of ATMs was shifted to NPCI. A number of innovations were developed culminating in UPI which was an instant payment system that was meant to be interoperable with Fintechs given the low levels of financial inclusion. The interesting aspect is the constant iteration driven largely by the need to drive inclusion that culminated in a global success story.

Complimentary developments around the fintech space have also played their part in creating de-facto open banking. The introduction of Jio lowered data costs significantly enabling more Indians to use the internet through their phones; proactive and forward looking regulations around data, payments and overall technology governance; and a growing fintech scene led by both global and local players such as Google Pay, Amazon, Facebook, Alibaba and Paytm.

Source: thedigitalfifth.com

Share of UPI payments;

Source: Credit Suisse

Some core considerations for African Countries

Competitive Structures in Banking

The market structure within banking is very crucial in the operationalisation of open banking. This should consider the relative power of banks in the overall economy and the relative concentration of power within the banking sector. Taking Kenya as an example, 7 of the 10 largest companies in the Nairobi Stock Exchange are banks. Granted the combined market share of banks in Kenya is around a third the market cap of the largest company Safaricom. Within the banking sector, the total deposit account market share of the top four is over 80%. This statistic is distorted by M-Shwari accounts that sit within NCBA. If one looks at the total deposit market share, the C4 is 40% which seems more competitive. Nonetheless, market power in Kenya as regards general influence is largely concentrated amongst the biggest banks.

What this does is create a situation in which there is little cooperation like that witnessed in New Zealand in terms of creating API standards and payments systems. Pesalink is a good example. If indeed there was robust cooperation, Pesalink would have been a giant by now. Nonetheless, it seems everyone wants to build their own proprietary infrastructure and extract rent from this.

The hybrid model of India could also be difficult to implement. UPI was built to enable interoperability within the payments system. In Kenya, the payments system is Mpesa. The Central Bank thus needs to build something that drives interoperability even with Mpesa and let the market innovate on top of this.

In Kenya a hybrid model seems to be the best solution. A purely regulator driven model could be slowed down by banks exposing non-scalable APIs and a market driven model would be impossible in the world of M-Pesa.

On the same point, I did an article sometime back arguing that banks in Africa are still very profitable and with lots of room to grow. It’s not generally in their interests to give up customer data to Fintechs.

Open Data as Opposed to Open Banking

The European and ASEAN models were based largely on markets in which financial inclusion i.e. adults with bank accounts is very high and the banking sector is mature and consolidated. In African markets particularly in East Africa have high financial inclusion within mobile money rather than the banking sector. Kenya for instance has overall inclusion of 80% but only 55% inclusion within a formal financial institution. Ghana has overall inclusion at 57% whilst only 40% inclusion at a financial institution.

Open banking in the sense of data portability for customers is thus not the only solution. These countries should adopt an open data approach with regulatory cross-collaboration by both the communications authorities and the Central Banks. MFIs and Savings and Credit Unions should also be roped in. The point is that customer financial data doesn’t exclusively sit with banks. Moreover, a large chunk of payments and payments data exists outside the banking system.

Mono for instance is working on enabling payments initiation and authentication via USSD for mobile banking led markets such as East Africa.

Access Initiation seems Lucrative in Market-Led Economies

One of the main issues surrounding open banking is that banks are finding it difficult to comply with API standards and have public APIs. This is expected because the bulk of legacy bank infrastructure was not built around having public API capabilities. Most of the API economy within the banking sector has been focused around internal APIs and specific partner based APIs.

The cost and complexity of creating public API’s whilst dealing with legacy tech issues is prohibitive especially when the benefits of open banking are not apparent. Abdul Hassan of Mono recently shared the following views in an interview with Tech Cabal.

“The banks need to be incentivized to share data because it is something they have to commit time and resources to...You might argue that the banks have to do whatever the Central Bank says but they might not do it in a way that is scalable” Commenting on a PWC report that stated that integrating to APIs takes weeks or months, Abdul had the following to say “The PwC report is probably wrong because it doesn’t take weeks or months; there’s nothing for you to integrate so it will probably take years. I would say that in terms of integration, it is nonexistent right now.”

The bigger the problem the more valuable the solution. Companies like Mono seem well placed to benefit from this. I see a situation down the line where Mono has worked out how to expose all APIs from banks and additionally offer data verification services. In such a scenario, nobody will care about banks having public APIs as Mono will have solved this. Plaid solved this for the US market and is now worth US$ 15 billion according to the latest fund raise.

DAPI is solving the same problem in the Middle East and North Africa whilst Prometeo is doing this in Latin America.

Open Banking - Short-term Hype but Long-term Riches

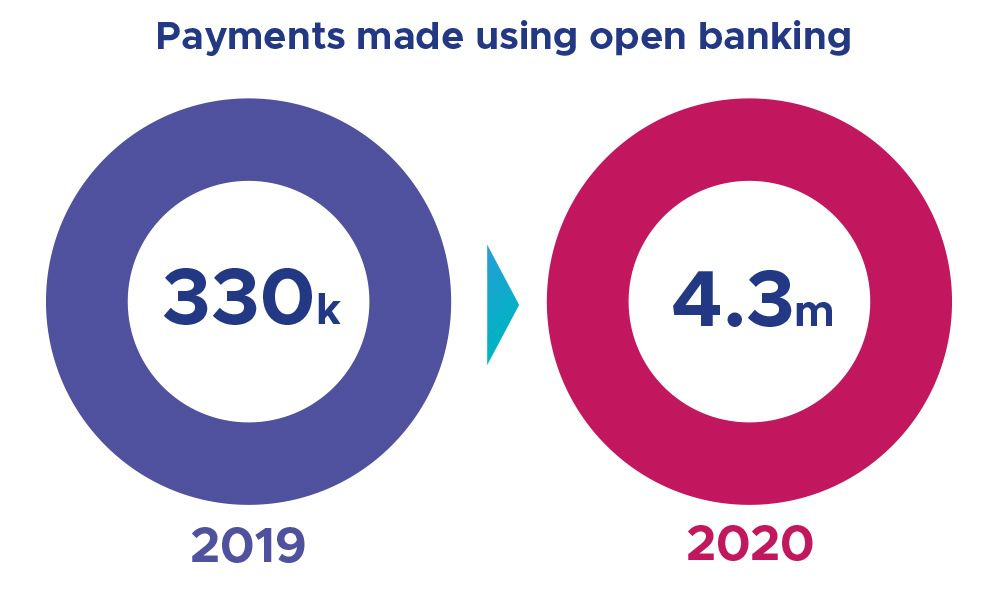

Like most technologies, the short-term is over-estimated but the long-term benefits are underestimated. Using the UK as an example, open banking has witnessed incredible growth. Total API volumes i.e. API calls grew to just below 800m calls in December 2020 from around 250m calls in December 2019. Total payments grew from 331,000 payments in 2019 to 4.3 million payments in 2020. In February of 2021 alone, payments volume were over 1m. This is very impressive growth and shows that open banking is working. It is conceivable that the same growth rates will be maintained and by 2025 open banking payments will be the default payment mechanism in the UK.

The success has been such that recently, HMRC awarded a contract to Ecospend to enable tax payments through open banking. This is a use case that is likely to drive more volumes.

Potential Approaches in Africa

Some of the benefits of open banking such as improved credit scoring, cheaper payments, digital identity and verification, income verification and others would add significant value to African customers. Nonetheless, the market approaches to open banking will have to vary.

I see a hybrid Indian example being useful in Kenya where the most critical thing in the interim is to solve digital identity and create an agnostic payments interface that can terminate into any stored value account. Access Initiation only needs to happen for the top 10 banks for this to take off since over 90% of deposit accounts sit in the top 10 banks. Equity and Coop bank have already embarked on creating open APIs. The same approach could work in Ghana where Mobile Money is significant.

In South Africa, a regulator led model could work due to their big 4 banking system as well as relatively higher rate of financial inclusion. The same reasons that made M-Pesa fail in South Africa are likely to make a regulator led model of Open Banking work there.

Nigeria has a regulator led model but the market dynamics seem to favour a market driven approach. The brilliant thing about Nigeria is that they have fixed their instant payments system through Nibbs and the Bank Verification Number system.

There is no one-size fits all model and market participants and regulators will have to find solutions that are relevant to their markets. However, the long-term benefits of open banking are significant particularly in Africa.

As always thanks for reading and drop the comments below and let’s drive this conversation.

If you want a more detailed conversation on the above, kindly get in touch on samora.kariuki@gmail.com;