#74 - Is it a Heist or Systemic Default: The Kenyan SACCO Crisis

Why mismanagement is baked into the Kenyan Sacco Industry, Why it's struggling in the 21st century and what the future looks like with Fintech in the Picture

Illustrated by Mary Mogoi - Website

Hi all - This is the 74th edition of Frontier Fintech. A big thanks to my regular readers and subscribers. To those who are yet to subscribe, hit the subscribe button below and share with your colleagues and friends. Support Frontier Fintech by becoming a paid subscriber🚀

For group discounts, write to me at samora@frontierfintech.io. If you can’t afford a subscription, consider referring a friend. The more you refer the longer your complimentary subscription is.

Reach out at samora@frontierfintech.io for sponsorships, partner pieces and advisory work. Spaces are becoming limited on my advisory hours. I help clients with market entry, market mapping, strategic insights, sounding board to founders and general advisory across Pan-African Fintech.

📢📢I’m carrying out a Reader Survey over the next month to get insights from you on what works, what I should improve, what you value as well as some information that would help me make Frontier Fintech a thriving Media Business. Please fill out the survey below.📢📢 It shouldn’t take more than 3 minutes of your time. To make it worth your time, I’ll give you a months free subscription for filling the survey

Sponsored by Oradian

Built for Local Realities

Scaling a fintech or financial institution in Africa means navigating unique regulatory, operational, and market-specific challenges. Many global core banking solutions—built with mature markets in mind—lack the flexibility to accommodate local realities. A prime example? Loan fee structures. In many African markets, lenders need the ability to amortize fees over the length of a loan—a feature that most global core banking platforms don’t natively support. Fintechs and banks are forced to rely on cumbersome workarounds or build expensive custom solutions just to meet everyday business needs.

Oradian solves this by offering a core banking system designed specifically for dynamic markets. Our configurable platform adapts to local requirements, allowing financial institutions to operate seamlessly without compromise. From flexible fee structures to regulatory-ready workflows, Oradian provides the infrastructure you need to scale efficiently. Stop forcing global solutions to fit local challenges. Discover how Fairmoney uses Oradian to power its advanced lending business;

TL;DR

Kenya’s Savings and Credit Co-operative (SACCO) sector is beset by systemic fraud and mismanagement, epitomized by the recent KUSCCO scandal. Historically, SACCOs grew under strong state support when mainstream banks excluded lower-income Kenyans, but as Kenya’s banking and fintech sectors modernize—with digital loans, money market funds, and user-friendly bank products—SACCOs’ traditional advantages are fading. Large-scale SACCOs suffer from principal-agent failures and weak regulation, leading to recurrent theft and questionable governance. While small, trust-based co-operatives and informal rotating groups (Chamas/Tontines) still have value, Kenya’s evolving financial landscape indicates that SACCOs, unless regulated like banks or fundamentally reformed, face a bleak future in competition with more innovative, technology-driven finance solutions.

Introduction

“I am, at the Fed level, libertarian; at the state level, Republican; at the local level, Democrat; and at the family and friends level, a socialist.If that saying doesn’t convince you of the fatuousness of left vs. right labels, nothing will.” - Nassim Taleb

In a twist of extreme irony, two years ago the Kenya Union of Savings and Credit Cooperatives (KUSCCO) posted an article on its website called “*State warns on Sacco fraud as Kuscco marks 50 years”. In the article, the Minister of Cooperatives in an event meant to mark the Golden Jubilee of KUSCCO, warned of fraud in the cooperatives sector and how the government will take stern action. KUSCCO, established in 1973, is the apex organization for Savings and Credit Co-operatives (SACCOs) in Kenya, providing advocacy, financial, and technical assistance to its members. Two years later, it has come to light that KUSCCO has engaged in the mother of all cooperatives fraud with executives from the organisation stealing over US$ 100 million from the organisation over a decade. That’s US$ 10m a year from an organisation whose balance sheet is a shade over US$ 200m. Whilst it's tragic to the cooperative movement in Kenya which is the largest cooperative movement in Africa and the seventh largest in the world, it’s a wake up call to the entire country about the future of the cooperative movement. Nassim Taleb’s quote comes in here, whilst the spirit of cooperation is critical, Nassim reminds us that this spirit works better at a micro level. As things scale, it’s better to trust the spirit of shared incentives such as the profit motive.

When I started my career all those years back, my mom was encouraging me to join a Sacco as this was the way her generation got ahead. In the 70s, 80s and 90s, Saccos enabled Kenyans to get an education, build houses and get access to decent financial services. It was therefore extremely logical for her to encourage her son to join a Sacco. My career started off in financial services particularly asset management and the logic did not add up for me. It was the 2010s and banking in Kenya had grown in leaps and bounds. Banks had sales staff camped across the city hawking not only accounts but loans. Moreover, retail financial services, particularly the ability to open stock brokerage accounts and mutual funds, was getting easier. In the company I worked for, one could open a Money Market Fund with as little as 2 dollars. As a young man with a bit of financial literacy, it was clear to me that the financial system in Kenya could enable me to achieve my goals. I wasn’t excluded and therefore the idea of joining a Sacco didn’t make sense to me.

This insight has always been at the back of my mind. Are Sacco’s going to make it? Is there a role for Saccos in a modern financial system?. Why does this issue matter for a Fintech newsletter? I recently wrote an article that went slightly viral about How to Evaluate a Fintech Market. The underlying thesis was that, the bigger the scale of market failure in a specific market, the bigger is the Fintech opportunity. Stablecoins are growing like a wildfire in Nigeria because of a broken FX market. Payment companies are growing in Egypt due to a bank-led payments market. Understanding fundamental issues such as the savings and credit market in a country enables founders, investors and incumbents to think clearly about how to approach the market.

In this week’s article, we will discuss the Sacco market in Kenya. We’ll go into how the Sacco movement grew in Kenya, the current state of the Sacco industry, the factors that are leading to massive theft and racketeering in the industry, the factors that are weakening their value proposition and what this all means for builders in the space.

History of Co-Operatives

Source: British Broadcasting Corporation

Co-operatives movements trace themselves back all the way to European co-operatives in the 19th century. These movements cropped up in newly industrialised countries like the UK and Germany as a result of modern working class citizens banding together to create support systems that would offer protection in the event of emergencies. In 1844 in particular, a group of 28 artisans and weavers formed the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers. Struggling with poor wages and exploitative merchants, this group pooled their savings to establish a consumer co-operative store. They sold basic goods like sugar, flour, butter and oats. A key part of this story is that they formed the Rochdale Principles which remain a bedrock of the modern cooperative movement. Rooted in the Rochdale movement, these cooperative principles emphasize open membership, democratic control, shared economic participation, autonomy, education and training, cooperation among cooperatives, and a commitment to community well-being.

In Germany, Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen (1818–1888) and Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch (1808–1883) pioneered credit co-operatives. Schulze-Delitzsch founded the first urban credit co-operative in the 1850s to help small artisans access affordable loans. Raiffeisen created rural credit unions in the 1860s, allowing farmers to pool savings and lend to one another, reducing reliance on loan sharks. These co-operative banks later inspired credit unions and SACCOs worldwide.

These later spread to France through “Mutuels” and the Catholic Church played a key role in the spread of co-operative movements in Italy. A key element of the co-operative movements was that they enabled co-operation and shared prosperity models particularly for people who had something in common particularly the type of communication. For instance, the Rochdale Society brought artisans and weavers. Similarly agricultural co-operatives cropped up as did mining co-operatives. It’s critical to keep this in mind when looking at modern Saccos.

Early Days of Co-operatives in Kenya

In Kenya, the unifying factor was agricultural co-operatives in a pre-independence era. These were co-operative movements based on white settler farmers who decided to unite under co-operative models to finance agricultural inputs and the distribution of their crops. The first co-operative was established in Lumbwa, present day Kipkelion. At the time, membership to co-operative movements was limited to white farmers only. In 1944, this was opened up to Africans and was enhanced by an ordinance in 1945, formally recognising African cooperative movements. In 1953, the Swynnerton Plan enhanced African participation in cooperatives as government policy. This is a critical point that helps one to understand why Kenya was such a core market for cooperatives. The Swynnerton plan was centred around driving the growth of African agriculture particularly cash crops which were a critical element for post-colonial trade engagement. Europe wanted coffee and tea in raw form as well as other crops such as pyrethrum to power their industries. To achieve this goal, it was important that Africans moved away from subsistence farming and towards cash crop farming. This required infrastructure, not only the infrastructure to get tea into the hands of British tea processors, but also the infrastructure to enable African farmers to access the inputs they need to produce.

Michael Blundell, Colonial Minister of Agriculture with Future President Mwai Kibaki and the late Kenneth Matiba - Blundell played a key role in implementing the recommendations of the Swynnerton Plan - Source The Standard

The Swynnerton plan set in motion the cash economy in Kenya as an entire swath of farmers now engaged in the modern trading economy. They earned cash and this cash was meant to enable them to cover their daily living expenses. The growth of not only Saccos but also Kenya’s internal remittance economy and subsequently M-Pesa can be traced back to such colonial economic policy. In a cash based trading economy, the demand for savings and loans would be high and Saccos would have a key role to play.

Post-Independence and an Aggressive Push Towards Co-operatives

‘If any society is to develop it must have capital for investments and this cannot come from without entirely but must also come from within . . . those who conceived this idea of forming a Co-operative Savings and Credit Society were not only trying to take care of financial problems but also trying to help in the Nation building. ‘Salary and wage earners in the urban areas who have so many demands on their earnings are faced with very many acute money problems and many find it extremely difficult if not impossible to make both ends meet in providing for their own needs and that one of their families. It is this connection therefore that this type of Co-operative Society may be of the greatest help.’ Speech by Masinde Muliro - Source FSD Research

As Kenya gained independence, the government saw co-operatives as a way of not only raising capital but unifying the country. Saccos could be used to unify people beyond their tribal groupings and create a sense of national solidarity. A number of deliberate actions by the government saw the expansion of the Sacco movement;

The government wanted to encourage savings to contribute to national development. A deliberate action was taken to use the term “Saccos” rather than credit unions as Savings had to come ahead of Credit;

It was decided to expand the market for Saccos beyond the agricultural sector to urban wage workers. In 1969, the government drove a program to encourage all government and parastatal workers to join Saccos. This saw the creation of Saccos such as Harambee Sacco (Civil Servants) and Mwalimu Sacco (Teachers). The task for driving the creation of Saccos fell under the Ministry of Co-operatives;

In addition to collecting savings, it was important to encourage saccos to lend to Kenyans as urban living created demands on peoples wages. People needed credit for personal growth such as buying land, building and financing education. Almost all urban Kenyans born in the 70s and 80s can trace their education to some form of Sacco finance;

The Boom of SACCOs (1980s - 1990s)

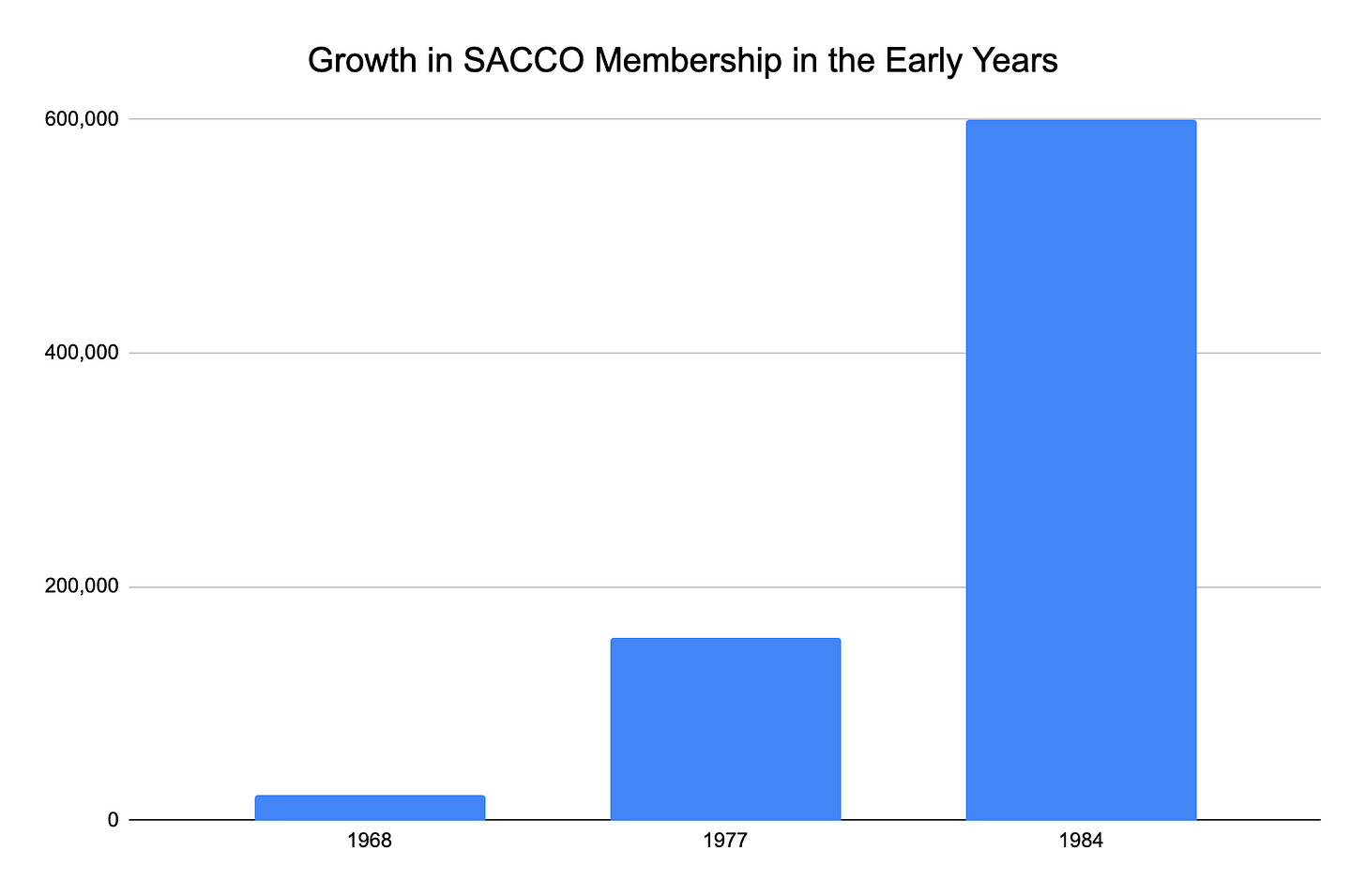

By the 1980s, SACCOs had transformed from small savings clubs into integral financial institutions within Kenya’s economy. Membership numbers surged:

Source: FSD Research

Co-operative officers received letters from groups of employees, asking for advice on creating SACCOs. They were also contacted by employers who wanted to help their staff create SACCOs. SACCOs were a popular movement – not just an official policy. In fact, officials in the Ministry of Co-operatives refused to register some of the suggested SACCOs, on the grounds that they thought they might not be stable. In particular, it became the policy that what was called the ‘common bond’ – the sense of community which all the members of the SACCO must share – should always take the form of working for a single employer. This policy was not rigidly enforced, but some groups who sought to create SACCOs were refused registration because officials decided that the common bond was simply not strong enough. - FSD Report on Saccos

SACCOs were no longer just urban wage earners’ institutions—farmers, transport workers, and religious groups also started their own SACCOs through an aggressive recruitment push by the Ministry of Co-operatives. At this period, the ministry was very strict on who could form Saccos and a core factor was that everyone had to either work in the same organisation or industry. These common bonds were thought to be critical for driving positive repayment behaviour.

“SACCOs have enabled a lot of workers to be able to purchase, at least, a house for themselves.” - Kenya National Assembly Debates, 1982

‘most of these co-operative societies have sprung up because of the difficulties or problems that wananchi (common citizens) face when they want to borrow money from the commercial banks’ - National Assembly Debates 1968

With government endorsement, SACCOs became workplace staples. New employees would be strongly encouraged (if not pressured) to join workplace SACCOs for financial security.

However, challenges emerged:

Loan defaults: With no collateral required, SACCOs relied on members’ sense of community responsibility to ensure repayment. However, some borrowers fled their obligations, leading to liquidity problems.

Mismanagement & corruption: Some SACCO officials gave themselves oversized loans and failed to repay, leading to collapses and mass member exits. A report from Thika Clothing Mills in the 70s showed that “In this society loans have been given that were never recovered since 1971/72. The former chairman . . . gave himself a loan in the tune of Shs 19,790/- which he stopped payment on 1st August 1973. From that date he has made no loan repayment or any share contribution at all. His share contribution stands at 3,100/- . Due to his bad management, so many members have inevitably resigned from the society.”

Government withholding of check-off funds: Government and parastatal employers deducted SACCO contributions from workers’ salaries but failed to remit them, causing financial crises in some SACCOs.

Workers at the Thika Clothing Mills in the 70s - Source Thika Clothing Mills

These cracks in governance and accountability led to the establishment of the Kenya Union of Savings and Credit Cooperatives (KUSCCO) in 1973, which aimed to train SACCO officials and provide oversight. However, KUSCCO itself struggled financially and was later taken over by the government in 1982. It was meant to be the lender of last resort to Saccos.

Liberalization & SACCOs’ Growing Pains (1990s - 2000s)

By the 1990s, Kenya underwent economic liberalization, and the government withdrew direct support for SACCOs.

"The government will no longer be involved in their day-to-day management as has hitherto been the case." - Sessional Paper No. 6 of 1997

This “hands-off” approach had mixed results:

Positives: SACCOs expanded rapidly, filling the gap left by failing commercial banks.

Negatives: Without government oversight, mismanagement worsened, and some SACCOs collapsed due to risky investments in real estate ("plaza mania").

However, despite financial sector modernization, SACCOs remained indispensable to Kenyans. At this period one must remember that banks were turning away Kenyans. There was an episode in the 90s where Barclays turned away every Kenyan who had less than KES 100,000 (US$ 1,000) in their bank account. People lined up to pick up the “little money” they had and go find an alternative. It was a moment of extreme embarrassment for Kenyans and Barclays never really recovered from a reputational perspective. Despite the increasing incidences of Sacco theft and collapse, they were the only game in town.

"People do not like banks... SACCOs are more friendly. You work with them, you eat with them." - Interview done by FSD

This emotional attachment kept SACCOs resilient, even as mobile banking and microfinance institutions emerged.

Modernization & Regulation (2010 - Present)

By the 2000s, SACCOs had evolved into major financial players, prompting calls for stricter regulation. The SACCO Societies Act of 2008 created the SACCO Societies Regulatory Authority (SASRA), tasked with professionalizing the sector. Saccos were central to the Kenyan condition but it was an industry plagued by mismanagement and liquidity challenges. The government had to come up with a way of formalising the sector and creating structure. It would have been more logical to convert Saccos into banks but Saccos were an entire polity unto themselves.

"If SACCOs are regulated like banks, what makes them different?" - National Assembly Debate, 2008

Key changes:

Separation of deposit-taking SACCOs (DT-SACCOs) and non-deposit-taking SACCOs.

Stricter financial reporting and capital requirements.

Reduction of risky lending practices through new governance structures.

This new regulatory framework helped stabilize SACCOs, but challenges remain:

Some SACCOs struggle to meet compliance requirements.

Digital banking and fintech competition are reshaping how SACCOs operate.

The risk of consolidation, as smaller SACCOs might be absorbed by larger institutions.

Today, Kenya has over 10 million SACCO members, demonstrating their enduring importance. Moreover, the total asset base of Saccos in Kenya is over US$ 21 billion with over 8,700 saccos both registered and un-registered. In terms of regulated Saccos, the number is 359 Saccos with a balance sheet of US$ 7billion.

The Sacco Headache and the Challenges Facing Them

This walk down memory lane is useful for it points out some key elements that have shaped the current Sacco industry in Kenya;

The government played a key role in its growth and therefore is emotionally and politically invested in ensuring the survival of the industry;

With over 10 million members, the Sacco industry has “Too Big To Fail” dynamics at least politically;

The industry has had a history of mismanagement and default almost from the very beginning;

The core conditions that enabled the industry to thrive included a traditional financial industry that was exclusive to the ordinary Kenyan. This dynamic has changed.

It’s therefore useful to review the factors in my view that drive my conviction about Saccos not having a key role to play in the future and what makes them so prone to mismanagement. The KUSCCO scandal is just but a micro-cosm of a larger issue. In 2020, Harambee Sacco, a civil servant Sacco had a US$ 30m gap in its books due to loan loss provisions that didn’t exist. Of its then US$ 80 million loan book, only 14.5% was actually performing. Over 10 years ago, Mwalimu Sacco, which represents teachers, engaged in a botched adventure where they sunk teachers' savings to buy a bank. This adventure ended in disaster leading to losses of close to US$ 20 million for teachers. So why are all these Sacco’s failing and what are the lessons to learn? It’s lazy to say that Sacco leadership is corrupt and they should do better. You always have to dig deeper. Why are banks well-run whilst they recruit from the same national pool of workers? Why do Nigerians in the US produce great doctors and technologists whilst Nigeria as a whole is mismanaged? It’s always lazy thinking to say “X People are bad”.

A Fundamental Principle-Agent Problem

This goes back to the Nassim Taleb quote about being a libertarian at the Federal Level and a socialist at the family level. The principal-agent problem is a cornerstone concept in economics and organizational theory, describing a conflict of interest that arises when one party (the agent) is entrusted to act on behalf of another (the principal), but their goals or incentives don’t perfectly align. In corporate governance, this tension shapes how companies—and especially banks—structure oversight, incentives, and accountability to ensure agents (managers, executives) serve the interests of principals (shareholders, depositors, or other stakeholders). George Akerlof’s contribution to the idea of information asymmetry in the 70s further sheds light on this issue where one entity, the agent has more information than the other entity, the principle.

In Saccos, the agents are the managers of the Sacco and the principles are the contributors to the Sacco, the members. In traditional banking, one of the ways this problem has been resolved is through regulation particularly;

Very detailed information disclosure requirements to the public as well as regular reporting to the shareholders and regulators;

A very robust audit framework by the regulator;

Rules around bank shareholding particularly limits on corporate ownership of banks and individual executive ownership limits. This is done to prevent insider lending.

Lastly the profit imperative for banks as opposed to the communal imperative has led to bank shareholders growing increasingly sophisticated. This enables shareholders to have the capacity to actually hold executives accountable particularly through boards. One of the ways this has manifested is in things like core banking upgrades where despite shenanigans still happening, bank boards are able to ask the right questions and drive the right outcomes. In the Sacco world, core banking migration or investment has been a key source of fraud and inertia. At scale, the principle-agent problem breaks with Saccos. An insider-outsider dynamic emerges where managers use their insider advantage to steal whilst outsiders, the members have no idea of what’s going on. This dynamic simply won’t go away. Theft in Saccos is baked into the system.

Regulatory Lacuna

Following on from the above principle-agent problem, there’s clearly a regulatory problem. The Central Bank oversees around 40 banks and a handful of Micro-Finance Institutions whilst having significant resources. The Sacco regulatory body on the other hand has to oversee over 300 Saccos with way less resources. This is an untenable situation that has to be seen in the context of the political imperative to keep Saccos alive given the investment that has already gone into building the sector. The Credit Union industry in the United States shows that fundamentally credit unions can exist with industry assets in excess of US$ 2.1 trillion. Nonetheless credit unions in the United States are regulated like banks. They have strict information disclosure requirements, participate in the federal liquidity system and have deposit insurance.

One angle could be to create regulation that shifts the onus on regulation to the Central Bank of Kenya once a Sacco hits a specific size, say US$ 50m in assets. The idea here would be tied to Taleb’s point and related to Dunbar’s number. At a specific scale, cooperation breaks apart. At this point it should be automatically regulated like a Micro-Finance Institution.

Nonetheless, one needs to see the regulatory lacuna for what it is. It’s there by design as it enables theft to happen. Leaders and politicians are smart and they have enabled sound regulation in the past. If a problem keeps persisting, you must always understand that a specific group wants the problem to persist as it benefits them.

The Maturity of Traditional Finance

A core theme throughout the growth of the Sacco movement in Kenya was poor banking services. All that started to change in the early 2000s with Equity Bank leading the charge. The seeds had been planted in the liberalisation push of the early 90s, but these seeds sprouted in the post Kibaki era. A mix of better regulation and a much improved liquidity environment led banks to focus on growing their loan books and the retail market had massive untapped potential. All of a sudden civil servants could access check-off loans very easily and SMEs were able to get working capital finance.

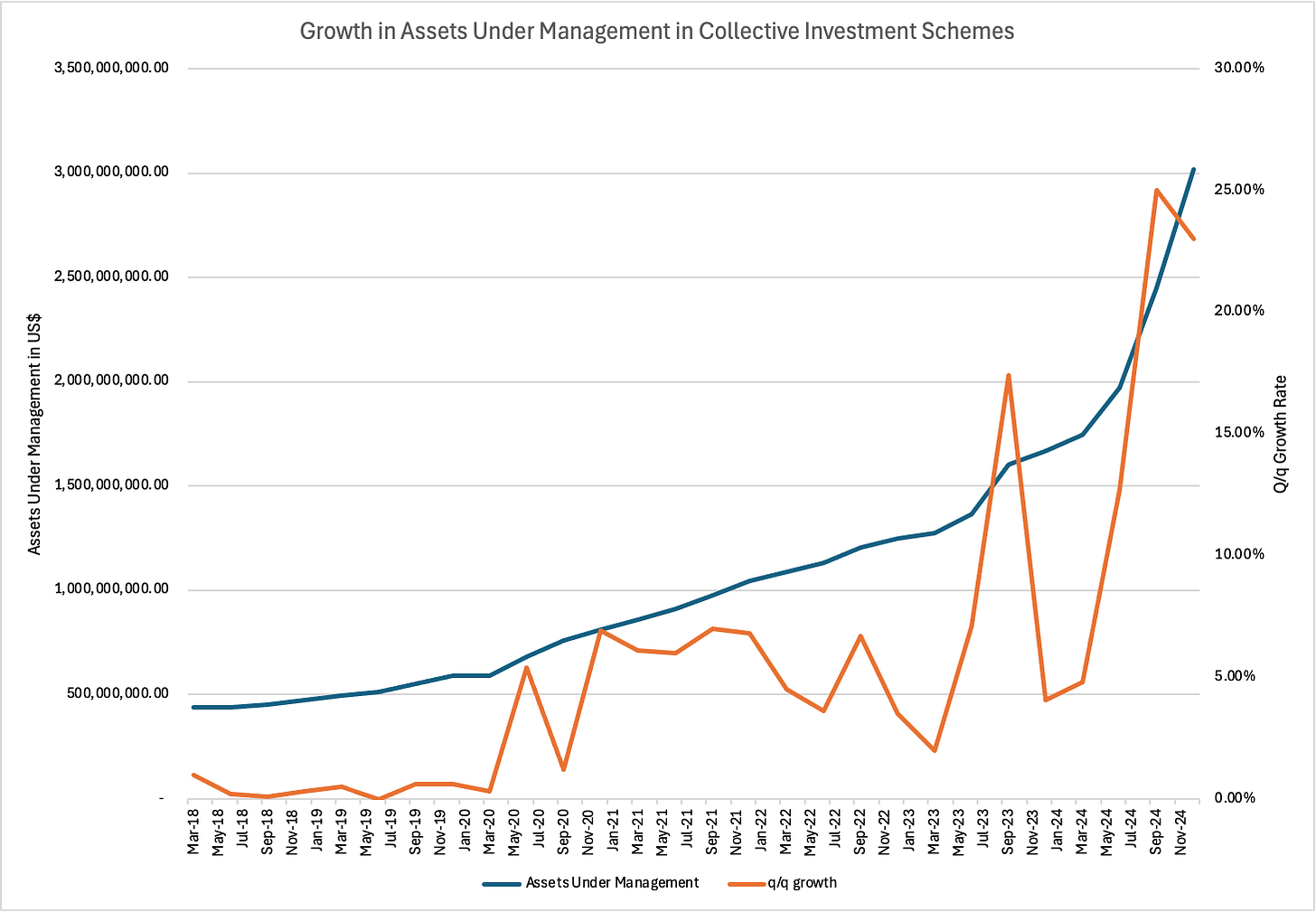

The chart above shows that the mutual fund is growing as a function of market education and awareness. Assets Under Management in Kenya’s mutual fund industry have grown from slightly above KES 50 billion or US$ 500m to over KES 329 billion or US$ 3 billion. Money Market Funds and Fixed Income funds account for 80% of these funds and both are essentially savings products given their focus on capital preservation. To put this into context, the entire Sacco industry had total savings of KES 680 billion or a shade over US$ 5 billion. People are more and more saving with money market funds which offer higher savings than banks. This is shown in the growth stats, quarter on quarter growth in total assets has been growing at a higher rate meaning that the industry is actually accelerating upwards.

One factor that has driven this growth is the increasing participation of banks in the industry with players like NCBA, Standard Chartered and Absa leading the charge. 15 years ago, banks were hesitant to push their asset management businesses because they competed for funds with their deposit franchises. Now, the industry has grown in sophistication largely due to customer demand. Banks are now offering loan products that are tied to the savings and assets held under the wealth division. This is the core promise of Saccos and now banks are starting to eat their lunch. The next step should be to offer loans that are not just matched by savings but that are a multiple of savings.

Digital Loans

Across the continent, urban dwellers are relying more and more on digital loans. In Kenya, players like Safaricom with M-Shwari, Branch and Tala are driving this charge. This is being augmented by players like Watu Credit and M-Kopa which are providing asset based lending that is delivered digitally. This is not just a Kenyan thing. The growth of the digital lending industry in India has weakened demand for Chit Funds and the growth of Ant Group and WeChat in China diminished demand for the Hui system which is essentially a Rotating Savings and Credit Association (Rosca) and works like Chamas in Kenya and Tontine’s in West Africa.

Digital credit provides the speed that Sacco’s provided but with less of a headache in terms of the application process. Digital lending now is not only a Digital Lender thing, banks are active in the space with propositions like Timiza and other digital loan products that rely on algorithms and internal bank data. As a young person, the mix of a robust savings system through Money Market Funds and digital loans really weakens the value proposition of joining a Sacco.

Urbanisation and the New Economy

What’s very clear from the history and growth of Sacco’s globally is that they were very much tied to occupational groups that emerged from industrialisation. The Rochdale group being a prime example. As the economy changes due to technology and digitisation, some of this commonality begins to fritter away. 40 years ago, it was very easy to group people into occupational groups. Now it’s not as simple. New jobs such as influencers, solopreneurs, global gig workers have all emerged due to tech with the borders that define occupations being more and more nebulous. A teacher can derive 100% of their income from teaching English or Art on the internet. What does that make the teacher, a solopreneur, a global gig worker, a teacher or all of them combined?

Moreover, this trend in labour is being accelerated by Urbanisation which naturally frays the social bonds that tied traditional Sacco membership together. Urbanisation tends to go hand in hand with individualism. This is not a Kenyan experience, there’s evidence that shows that urbanisation had a key role to play in the weakening of the Hui System in China due to the weakening of these social ties.

What does the Future Look Like

The lack of clear regulation and the insider-outsider dynamic in Saccos is endemic to the sector. This won’t change. So long as this doesn’t change and coupled with an ever improving banking sector, the growth of digital banking, the fraying of societal bonds due to urbanisation and the ever changing dynamic in modern labour, then the outlook for Saccos is bleak. Nonetheless due to path dependence, it’s difficult for the government of Kenya to demand banking regulation for Saccos. I think there’s a very clear nexus between the political world and the never ending looting of Saccos. My initial intuition about Saccos when I was starting out my career has proven prescient at least to me.

However, how should leaders, investors and Fintech founders think of the gap that Saccos fill and how you should build businesses around this?

A Libertarian at the Fed Level and a Socialist at the Family Level - Chamas and Tontines across the continent have continued to thrive. In India, the Chit Fund system has also done well despite excessive regulation. A key element of these Rotating Savings Systems is that they’re often small enough for shared trust to emerge. It’s easy to govern through trust when you’re 10 people who live or work in the same area. It gets extremely difficult to scale this trust when you’re 10,000 of you in a Sacco. Chamas will continue to thrive and the opportunity for providing digital tools for the management of these groupings will continue to be viable for both banks and Fintechs. Nonetheless, one must always remember that their analogue nature is core to their design and success;

Banks and Neobanks need to embed the value of Saccos to their Customers - Specifically merging savings and lending in a way that makes intuitive sense to customers. The attraction to Saccos in Kenya is that they offer high savings rates and low lending rates. Although from a financial perspective this is not good for Saccos, it’s a core attraction for clients. Now that banks are offering high yield savings and wealth products, the next step is to provide credit services that leverage these assets. A start is linking a credit card balance to a store of value product like a money market fund, mutual fund or even an insurance product;

The Growth of Onchain Finance - A number of entrepreneurs are building on-chain finance products that run on Stablecoins as the unit of account. These are essentially crypto-native neobanks that enable their clients to benefit from international money movement through stablecoins but with on-off ramps for day to day use. The benefit of crypto-native banks is that they offer digitally native workers a global payments solution that further enables accountability through the blockchain. Whilst the latter is a theoretical claim, the point is that crypto offers regulators and investors a better mechanism to create in-built transparency. I was speaking to someone from Tether the other day and they shared an interesting stat. In Kenya alone, USDT does over US$ 250m in monthly volumes and the bulk of this is in satellite cities like Machakos, Nakuru, Mombasa and Kisumu. The on-chain economy is growing and will likely facilitate banking-like services for the growing digital economy.

In summary, I’m not long Saccos despite the great work they keep doing for many Kenyans. Fundamentally, the principle-agent problem becomes too big at scale and the solution is to have them being regulated like banks or MFIs. The Fintech industry will continue diminishing the value of Saccos through the provision of digital lending, embedded lending and the unification of wealth management and financial tooling. As always with Frontier Fintech, when I talk about Fintech I talk about the merging of Finance and Technology and not a type of organisation. Therefore, a bank doing Fintech will be referred to as a Fintech in this newsletter. If you’re a Fintech, think through how to solve the problems that Sacco’s solve for clients and slowly start building around this. For instance, Watu Credit in the 80s would have been a Boda Boda Sacco. Nonetheless now, it works best as a standalone embedded lending play. The principle-agent problem is solved by having sophisticated lenders and sophisticated investors.

One challenge in Africa is that we always internalise our issues and never see them as part of a larger global trend. When the manufacturing sector declined in the 90s and 2000s, people blamed poor governance and very little was said about declining competitiveness, a growing China and a boom in global trade. Similarly, the lessons from the decline in Sacco type organisations globally due to digital lending and a growth in banking will be ignored when we’re analysing the future of Saccos. The outcome is that we’ll have a zombie industry propped up by nostalgia rather than hard core economics.