#41 SME Neobanking in Africa

Exploring the space and delving into insights from Sola Akindolu CEO of Brass

Hi all - This is the 41st edition of Frontier Fintech. A big thanks to my regular readers and subscribers. To those who are yet to subscribe, hit the subscribe button below and share with your colleagues and friends. 🚀

Introduction

SME Neobanking has become a very attractive space for investors and founders. Open recently raised US$ 100m from Temasek and Google amongst others to build out a Neobank for Indian SMEs. Qonto based in Europe is in plans to raise US$ 400m which will value the firm at US$ 5.02 billion. Novo, originally from New York and now based in Miami concluded a US$ 41 million series A mid-this year. All these added to the mega rounds that were done by Revolut and Mercury earlier this year.

These businesses are based on creating digital banking capabilities catered to SMEs and delivered through intuitive apps and web platforms. Features vary from market to market but mostly centre around; payments both acceptance and initiation, cash flow management tools, integrations to third parties such as accounting and tax as well as more intuitive digital lending capabilities. The feature set differs according to the markets in which they’re operating. In Africa, Carbon, Kuda Bank and now Brass are leading the way in Nigeria in terms of SME Neobanking. In South Africa, Tyme Bank is the leading Neobank offering an every-day business account for SMEs. Yoco, starting off with mPos machines, is evolving into a wider set of financial services for its SME clients.

Banks are not being left far behind, according to a 2019 EIB study, over 60% of African Banks surveyed mentioned that SMEs are their core strategic priority. Banks in Africa are slowly shifting away from their traditional Multinational and large local corporate clientele and towards retail and SME banking. Recent moves by large banks such as GT Bank, Standard Bank, Ecobank and Equity Bank confirm that banks are spending more energy on the SME Space. Equity Bank for instance recently launched a single “Till Number” with a view towards garnering more SME business.

This article will explore the space, understand what exactly SMEs are, their banking needs, whether the SME space or building out SME capabilities is really useful and what it will take to win in this space. I also chat with Sola Akindolu, the founder of Brass which recently raised US$ 1.7m to build out an African SME proposition.

SME’s in Africa

The terms Small and Medium Enterprises (SME’s) or Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME’s) are often used interchangeably. A common definition is hard to form a consensus around as it’s often a very local thing. A Medium Enterprise in the USA would be a large corporation in Africa.

To get around this taxonomical quandary, most statistical agencies define local standards that centre on key metrics such as number of staff, annual turnover and how many assets these SMEs have. Looking at Nigeria and Kenya, in terms of annual turnover, a small company in Nigeria is expected to have a turnover of less than US$ 48,000 per annum compared to US$ 4,500 in Kenya. A medium company is expected to have a turnover of US$ 1.2 million in Nigeria compared to US$ 895,000 in Kenya. Both countries are pretty similar in terms of the number of employees.

Source: Central Bank of Kenya, BOI Nigeria and SMEDAN

In terms of assets, according to data from the Central Bank of Kenya, medium companies are expected to have assets of US$ 2.2 million in Kenya if they’re in manufacturing and half of this if they’re in the service industry. In Nigeria, medium sized SMEs are expected to have assets of US$ 1.1 million.

In terms of contribution to GDP, SMEs account for over 96% of total businesses in Nigeria and contribute around 50% of national GDP whilst accounting for 84% of all jobs. In Kenya, SMEs contribute around 33.8% of GDP according to the 2016 Economic Survey whilst accounting for around 90% of the jobs being created annually. In South Africa, SMEs account for 99% of all businesses and 52% of GDP whilst accounting for 29% of employment.

Globally compared to the USA and countries such as the UK and Germany, the statistics around contribution to GDP, employment and percentage of businesses, the numbers are pretty similar.

In terms of commercial characteristics, 73% of SMEs in Nigeria are sole proprietorships and this number is similar in Kenya. The reason for this is that most SMEs in Africa are at the micro-level of entrepreneurship i.e. low turnover and few staff and thus most prefer sole proprietorship or are too small for any other structure. Most SMEs are in the retail trade including the repair and servicing of motor vehicles. In fact, in Kenya over 74% of SMEs are in the service sector.

In terms of access to financing, only 5.4% of Kenyan SMEs responded to having accessed bank based financing in the 2016 SME survey. Over 80% reported family and friends as the main source of financing. In Nigeria, according to a recent PWC survey, only 16% of SMEs reported having received credit from formal financial institutions. Nonetheless, according to a recent Central Bank of Kenya SME survey, 20% of bank lending was to SMEs compared to only 1% in Nigeria. This could be down to two things, banks in Nigeria have higher concentrations around large corporate clients particularly around oil and gas. Secondly, Kenya is a more diversified economy and thus banks have optimised around both retail and SME propositions better than their Nigerian peers. South Africa has similarly a higher concentration of lending to SMEs, in fact according to the SARB, SMEs accounted for 28% of total business loans.

In terms of the main challenges faced by SMEs in Africa, they can generally be categorised as;

Lack of access to markets and customers, often categorised as the biggest hindrance to SME growth;

Inefficient and often complex regulatory environment revolving around a maze of local and national bodies who often don’t communicate with one another. In Nigeria, this was cited by 57% of SME’s surveyed by PWC as the largest constraint. In fact, it takes around 343 hours to comply with tax laws and businesses have to make around 48 tax payments per year;

Access to finance is a major issue both for working capital as well as capex - it is estimated that there’s a US$ 330 billion SME funding gap in Africa and a global SME funding gap of US$ 5.2 trillion. I did an article on SME funding that delves exclusively into the issue of SME funding in Africa;

The lack of skills and expert labour;

Cash flow constraints often brought about by poor accounting practices and lack of visibility into a business’ cash flows. The issue is mainly around understanding both accounting and economic profit as well as separating personal accounts and business accounts.

Why Should we Pay Attention to SME’s

My general view of this has been defined in previous articles and is based on the Theory of the Firm by Ronald Coase. The general idea is that there are transaction costs that exist that prevent the market from efficiently allocating resources within the economy. Firm’s therefore exist to better allocate resources towards achieving a larger objective. For instance, firms can allocate resources such as labour towards specific objectives such as a new project or a different department so as to align with market incentives. These re-allocations of labour can be dictated upon the participants in this case staff, based on their employment contract.

Similarly, the Theory of the Firm explains why companies have in the past integrated along the value chain. Companies such as Lafarge, East African Breweries and other large multinationals controlled the full value chain from logistics, warehousing, distribution, sales and marketing as well as general administration. The contracts between the different departments within the organisation are defined by the organisation and thus can be relied upon.

Within Africa, due to the lack of contract enforcement by national law as well as poor property rights, firms and industries organised around networks. These networks could be ethnic based networks along a specific commercial opportunity. The Ashanti for instance in Ghana are known to control the Cocoa trade. In East Africa, the Indian community is known to control trade and light manufacturing within the region. Similarly, Lebanese trade networks are dominant in West Africa. Elements of retail trade in Kenya for instance, the Gikomba market is also largely ethnically oriented. The key idea is not much based on ethnic bias in a negative sense, but a kinship that binds commercial agreements and can be enforced based on “exclusion”.

The passage below from a 2006 World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, sheds light on the analysis above;

As the formal legal system is unreliable for settling commercial disputes and costs of search and verification are high, firms trust their long-term customers and suppliers to… pay their bills and deliver quality products on the prospect of future business. Trust is built on a history of successful, repeat transactions. The RPED surveys show, for example, that firms generally deal with a single supplier of a particular input on a regular basis (even when they have a choice among sources of supply) and the average length of relationship exceeds seven years...But, as many economic activities require dealing with different partners at different times and cooperation is more easily sustained in relationships if sanctions for opportunistic behavior come not just from the business partner who has been cheated but also from other firms in the business community, business and community networks are formed to govern transactions.5 Self governance in such networks works by sharing information on non-delivery, late payment, and default via a multilateral reputation mechanism, supported by a framework of credible commitment, enforcement, and coordination.

SME’s plug into these informal ethnic networks along the value chain. For instance, an SME can plug into a hardware network and develop supplier credit with the wholesaler based on repeated transactions. These repeated transactions drive trust with the ultimate contract being enforced through self-governance principles based on the community. Potentially, this is why the percentage of bank financing to SME’s is lower in low trust societies.

Having understood this, one then has to understand the impact that technology is having on commercial transactions. The network problem defined above as well as the Coase theory of the firm which largely applies to larger organisations in essence is a data problem. Because you don’t know how a counterparty will perform and you don’t know how other counterparties perform, it makes sense to internalise that transaction. This data problem is the foundation of the modern gig-economy. Using ratings based on previous transaction history, users can trust that the counterparty will perform as expected. Whereas previously, taxis were either controlled by a private company or through a centralised licensing agency (New York Taxi Medallions), Uber reimagined the industry by introducing both driver and rider ratings thus creating transactions.

In China, Alibaba solved the trust problem by introducing both escrow as well as a similar rating system thus enabling transactions to happen between strangers. This data problem is being solved across multiple verticals and is being accelerated by the “democratisation” of multiple industries. AWS enabled software companies to form, particularly SaaS businesses. Twiga in Africa is democratising access to “stock” for shopkeepers enabling anyone to have access to multiple products, which in the past needed “community/network based” access to wholesalers. The internet has also created the era of Direct to Consumer brands, “Shein” in China is the posterboy of this trend.

The outcome of all this will be a growth in SMEs, whereas the 20th century was the century for corporations, my view is that the 21st century will be the century of smaller businesses and solo businesses. The best example is my newsletter and a host of other small media businesses. My friend Adelle Onyango of the “Legally Clueless” podcast is a great example. She quit her job at Kiss FM and has gone on to build one of Africa’s top podcast as well as a growing media business. The internet has democratised a lot of the resources that were previously owned and controlled by a corporation. This includes, access to an audience, production and distribution infrastructure as well as business administration and management infrastructure.

Substack has also created an opportunity for people like me to build a media business. Frontier Fintech can be both a global Fintech publication as well as a global business publication across all forms of media; audio, video and print. I don’t need much in the way of staff as software can handle a lot of the day to day staff that previously needed numerous bodies.

The SME Neobanks

Stepping into the fray are new Fintechs that are building around this global trend of Neobanking. Different players have emerged to cater for different opportunities. Firms are mostly building around specific frameworks, Revolut and Wise are building a product for SMEs that conduct their businesses globally and have global payroll. OakNorth in the United Kingdom is targeted at medium businesses and is leading with lending products based on the observation that bank underwriting practices are based on standard frameworks that don’t work well for SMEs. WeBank in China is also leading with algorithm based lending to underserved SMEs. Firms such as Mercury are building for specific client bases such as start-ups and tech companies. Holvi in Europe is targeted at self-employed individuals in Europe.

In terms of product, most of these Neobanks are based on some standard capabilities such as;

Basic business accounts;

Card issuance and management for employees including spend management;

Payments acceptance and initiation across specific networks e.g. UPI payments in India or NIBSS payments in Nigeria;

Advanced reporting and dashboards for cash in and cash out to improve working capital management;

Additional feature sets include;

Integration to accounting software such as Quickbooks and Xero;

Integrations to local entities such as business registration and tax authorities;

Marketplace integrations, a good example being Starling bank;

The images below show the different integrations done for Asian, American and European SMEs;

In Africa, a lot of SME’s use Mobile Money as their front-end for financial services particularly cash in and cash out. Safaricom has built out the M-Pesa for Business app that has a better interface as well as improved analytics. Banks have built out their own propositions with regional leaders such as Equity Bank, KCB, GT Bank, Ecobank and Standard Bank all having an SME proposition. Players such as Flutterwave and Paystack have also built out consumer facing apps that act as SME Neobanks. Flutterwave has Barter which in turn has a lot of the back-end functionality that Flutterwave has built including their stores concept.

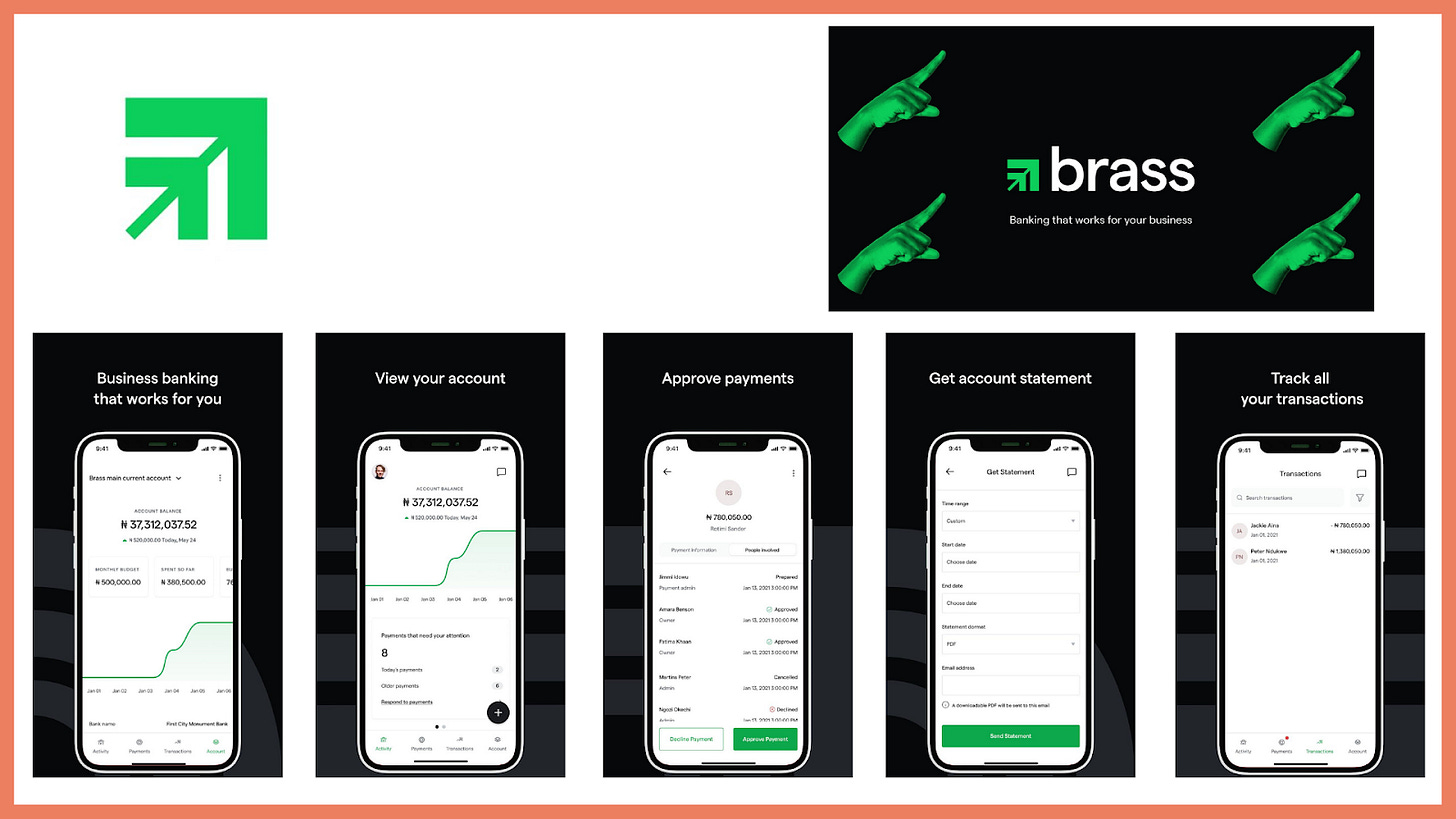

Insights from Brass Banking CEO and Co-Founder Sola Akindolu

Brass recently raised a US$ 1.7 million seed round to grow their SME proposition both in Nigeria and across the continent. When I spoke to Sola, he was in Nairobi where he’s working on launching a proposition for the Kenyan market. What impressed me about the Brass seed round is that it was financed by local tech entrepreneurs including Olugbenga Agboola of Flutterwave as well as Ezra Olubi of Paystack. This shows that Nigeria is quickly developing an ecosystem.

Why Brass

Brass has been in existence for around 18 months. Sola has a background in product with his most recent experience being Head of Product at Kudi. Together with co-founder Emmanuel Okeke (a former engineering manager at Paystack), Sola noted that Brass started with the basic idea that “that we can build a world class financial services business for African businesses and if we’re able to do that, we’re going to drop the barrier of entry for a whole lot of businesses to start and be successful”. In essence, the experience of an SME in terms of accessing and consuming financial services is very arduous, largely based on an inaccessible banking system.

Competitive Advantage

According to Sola, there will be space for banks and for Fintechs in the African financial services ecosystem. Being from a technical background, Brass can deliver on product innovation at a pace that no bank in Africa can. With a basic account which is a commodity across the financial services space, Brass has been able to rapidly build out capabilities such as cash flow management and forecasting, expense management and control, payroll and a whole host of other functionalities. The future product roadmap is exciting and will include features around tax payments and planning.

From a technical perspective, Brass has built out their own ledger capabilities i.e. core banking platform. The idea behind this is that they want to maintain a composable framework where they combine best of breed capabilities. For instance, Brass can easily switch between Paystack and Flutterwave for payments depending on a number of factors.

In terms of distribution, Brass has built out off-line capabilities which are essentially customer servicing centres. Africa is still off-line and thus touch points are important. Brass’ touch points enable account opening and basic customer service but they don’t handle cash. Interestingly, Equity Bank have often talked about converting their branches into SME service centres offering services such as wealth management and business advice.

In essence, Brass is betting on world class product capabilities combined with a widespread, low-cost, off-line customer servicing network to grow business.

Main Businesses Served;

Brass is seeing traction largely from Sole Proprietorships and largely urban small businesses. These are boutiques, upscale shops and services businesses such as barbers and salons as well as tech-enabled or powered small businesses. The clientele is largely well-educated and tech savvy.

For the lower or mass end of the spectrum, the opportunity is large nonetheless Sola notes that a lot of market education is still required to convert the market. Most people still think that a bank needs to have a large head office, big branches and intimidating security guards. This is a long-term problem. Luckily, all tech companies are jointly solving this problem. Market education has positive externalities, one company's efforts to educate the market on the benefits of tech adoption, creates positive externalities for all tech companies.

On Integrations to Local Government

Sola was very clear that one of the main jobs to be done revolves around lowering the barriers to entry for business to start and successfully operate businesses in Africa. In his words, African businesses face existential challenges on a daily basis and thus Brass will be successful if it makes other businesses successful. As mentioned earlier in the article, the complexity of adhering to local taxes and regulations is the biggest problem in Nigeria. This issue is faced across the continent.

Working and integrating to local and state authorities is very critical in any SME’s product journey. According to Sola, this is a leverage issue. If you have 5,000 customers who need a specific product, then it’s easier to approach any agency and seek to integrate so as to solve a pain point for your clients.

Challenges

Despite the incredible from the likes of Sola at Brass and many others in Africa, some challenges still persist;

Regulation - African regulators are yet to create standard frameworks for digital banking licenses that enable fully virtual banks. Singapore is a good model to build around;

There’s an infrastructure deficit in terms of the infrastructure required to power a Neobank. There’s a dearth of Partner banks that can enable Fintechs to build around. This is both a skillset and technology issue. In addition to partner banking, there needs to be infrastructure that supports commercial identity verification, payments and credit scoring. Some need a holistic government level approach rather than singular private sector solutions;

Market education as Sola mentioned is also a major challenge. This is compounded by the fact that Africa is a low-trust society so “better the devil you know” still dominates SME thinking towards their banking relationships

All that said, the future is bright and in my view, players like Brass in 10 years time could be large multinational banking entities with impressive economics due to their digital native nature.

As always thanks for reading and drop the comments below and let’s drive this conversation.

If you want a more detailed conversation on the above, kindly get in touch on samora.kariuki@frontierfintech.io or samora.kariuki@gmail.com

Great work Samora, I love all the write up, they are well researched and written keep it up!