#69 - India's Supply Chain Finance Revolution

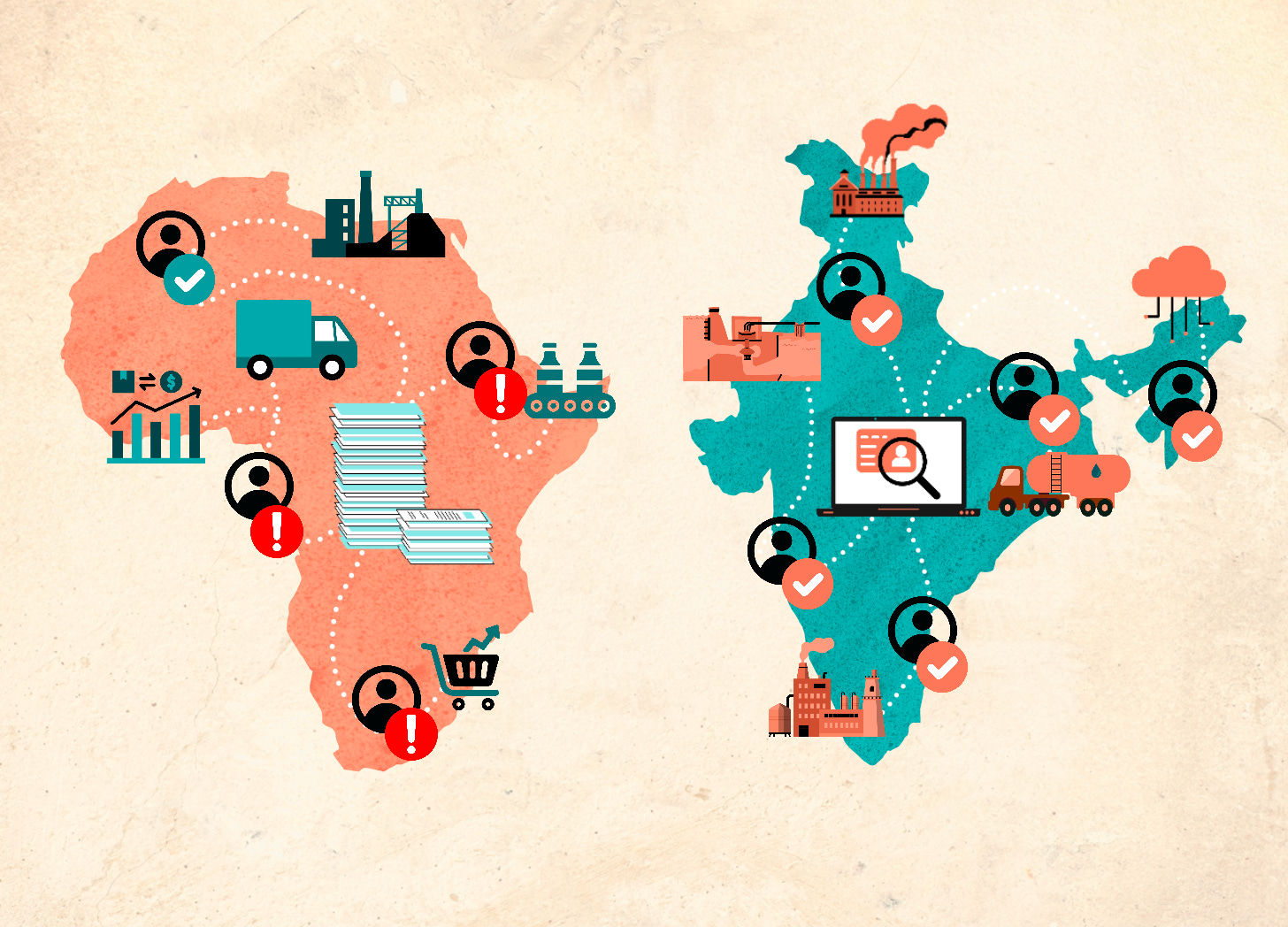

A look into what lessons Africa can learn from India's successful SCF revolution over the last 10 years. Also, an overview of some of the key Fintechs involved.

Illustrated by Mary Mogoi - Website

Hi all - This is the 69th edition of Frontier Fintech. A big thanks to my regular readers and subscribers. To those who are yet to subscribe, hit the subscribe button below and share with your colleagues and friends. Some of Africa’s leading operators rely on Frontier Fintech for regular insights🚀

For group discounts, write to me at samora@frontierfintech.io. If you can’t afford a subscription, consider referring a friend. The more you refer the longer your complimentary subscription is.

Reach out at samora@frontierfintech.io for sponsorships, partner pieces and advisory work. Spaces are becoming limited on my advisory hours. I help clients with market entry, market mapping, strategic insights, sounding board to founders and general advisory across Pan-African Fintech.

Sponsored by Skaleet

A Flexible, Low-Commitment Addition to Your Existing Core

In an ever changing commercial environment, vendor lock-in is a drag on growth and innovation. Switching costs and vendor lock-in are common barriers to adopting new platforms. Skaleet’s model addresses this by allowing banks to adopt its platform as a low-commitment addition, working alongside legacy providers without disrupting existing vendor relationships. This flexibility means banks don’t have to terminate existing contracts or make long-term commitments with Skaleet to realize the benefits of a digital-only solution.

Skaleet also provides a transparent, predictable pricing model and a lower total cost of ownership. Compared to the heavy customization and maintenance costs of legacy systems, Skaleet is cost-effective, providing banks with a digital innovation platform without the operational burdens of a full migration.

The team will be in Nairobi, Tunis and Dar-es Salaam between now and February. Schedule a call or meeting below.

Introduction

Competitive SMEs

Working in the African logistics space particularly at the intersection of finance and logistics, I got a front row seat to how working capital is such a major issue for African businesses. I came to the conclusion that sorting out working capital has the potential to double the size of Africa's economy given the amount of cash tied up. Let’s make this a bit more concrete. One of the clients we were serving was an innovative manufacturing company. They used advanced manufacturing techniques particularly Computer Numeric Control (CNC) to manufacture bespoke steel and aluminium equipment. Some of their clients were large auto assembly plants and various other sizable manufacturing companies. For instance, they’d manufacture the aluminium or steel parts that go into making seat frames for trucks or wiper blades.

Upon producing and delivering the parts, they’d have to wait between 60 and 90 days to be paid, a time that felt like an eternity for a small but growing manufacturing company. My interaction with this company and many similar enterprises disabused me of the notion that African SMEs were by and large uncompetitive. Here was a company built by engineers doing interesting work and getting large industrial clients such as Stihl, Bosch and others. Given the issues around currency availability and the natural drive to promote local business, they offered large manufacturers, particularly MNCs the ability to localise their supply chains. There was just one challenge, they needed working capital to grow. To have this discussion, it’s important to make the notion of working capital more vivid.

The Working Capital Trap

Say that this business had turnover of US$ 2m and had to wait 90 days to be paid by their clients (Receivable days), they’d need approximately US$ 500,000 in working capital to support this turnover. This is simply the amount of cash the business needs to have to cover the time between when it makes a sale and when it collects from the sale. It’s simply calculated as 90 divided by 360 = 1/4 multiplied by the turnover. Assume the business has this cash which is a massive assumption, the challenge will then come with growth. If the company grows its turnover by 50% in the next year, then they’ll need US$ 750,000 in cash at hand to support the business. The working capital demand grows by the same factor as the business.

Now, at some point given that the business has fixed inputs i.e. manufacturing capacity, it will face a situation where it not only needs working capital, it will also need investment in fixed capital i.e. more manufacturing capacity be it machines or buildings for it to continue to grow. As always in economics there’s no free lunch and therefore it can either keep its cash as working capital or invest it to expand capacity. In advanced economies, how this is solved is that they’d be given a working capital line by their bank or would be part of a structured invoice factoring program that enables them to get immediate payment. This additional capital can then be leveraged to expand their manufacturing capacity. This expanded manufacturing capacity goes directly into GDP figures given that they can move from manufacturing say 1,000 parts per year to 3,000 parts per year.

The Ripple Effect on the Economy

This company’s struggle is emblematic of the challenges SME’s face across the continent. Most banks they’d approach would only support their working capital requirements if there was underlying physical collateral. Given the analysis in the prior paragraph, if they indeed had collateral worth US$ 500,000 to support the loan, then their growth would be severely limited as it can only be supported by the owners of the businesses dipping into their own pockets.

Similar cases abound across Africa’s economy where businesses are in a growth trap of sorts. Charging for growth means investing way more in your business than you would have to in other markets. The end result is;

Lower Returns on Equity;

Stagnant SME’s - No growth;

Uncompetitive economies given large well capitalised companies dominate;

Very little investment (fixed capital formation) given money is tied up in working capital;

Unlocking value trapped in supply chains is therefore a very important job to be done and is something I think about a lot.

To this extent, I have spent time studying India’s Supply Chain Finance boom and the factors that made it tick. Studying India’s success in SCF can be productive to unlock growth in the continent. This article explores how India’s success in Supply Chain Finance (SCF) can serve as a blueprint for Africa to unlock working capital for SMEs, drive economic growth, and address the challenges of financing in supply chains. It will look at; India’s Success, Why it matters for Africa, The factors that enabled India’s SCF boom, the key players in the market and what lessons are to be learned for the continent.

India’s Supply Chain Success

Supply Chain Finance (SCF) is a mechanism that improves cash flow by enabling suppliers to receive early payment while buyers extend payment terms. A financier pays the supplier upfront at a discount, and the buyer repays later. This benefits suppliers with quick cash, buyers with optimized working capital, and financiers with transaction fees, creating a win-win solution for all parties. For instance in our example of the Parts Manufacturer, an SCF provider could enable the manufacturer to get cash upfront rather than wait 90 days at a small fee.

For Africa, it would be useful to look at India’s recent success and try and learn from this. Various estimates put the size of India’s SCF market at between US$ 10 billion and even US$ 100 billion with a CAGR over the next 5 years being estimated at 30%. The variance in the estimates can be disconcerting but the evidence points to the amount being closer to the mid-point i.e. US$ 50 billion. For one, according to BCR Reports, the overall SCF market in Asia is estimated at US$ 486 billion as of 2023, given that India accounts for roughly 10% of Asia’s GDP, then a US$ 50 billion estimate makes sense. Moreover, the growth is a factor of the size of the market compared to the size of the economy. For instance, the US has an SCF market worth roughly US$ 1.2 trillion or 4.5% of GDP. India’s SCF market on the other hand is only 0.32% of the market.

Nonetheless, India has been a relative success story over the last 5 years. Companies like Veefin processed US$ 1.3 billion in monthly transactions and KredX, another supply chain finance platform does around US$ 600 million in monthly disbursements with over 700 corporates served. By May of last year, India’s Trade Receivables Discounting Platform (TReDS), an initiative of the Reserve Bank of India had facilitated invoice discounting transactions worth US$ 11 billion or INR 1 trillion. An incredible achievement. On the banking side, SBI and HDFCs own digital SCF products have achieved US$ 2.3 billion and US$ 1.7 billion in SCF volumes respectively.

A story is told of an Indian engineering firm called BTL EPC Ltd which has seen its revenues and profits double due to using RBI’s TReDS platform. Moreover, their cost of funds has reduced by 250 basis points. A situation that the Kenyan manufacturing concern would want to be in. The CEO of M1Exchange, a platform on TReDS says that SME’s can benefit from interest rates of 7-10% compared to the 16-25% they’d get at banks.

The diagram above shows volumes of invoices financed through TReDS in those specific months in US$. On average, 95% of the invoices uploaded get financed. The number of registered SMEs have grown from 13,342 in March 2022 to 40,387 in December 2024.

The result of all this has been the growth of SCF platforms in both revenue and valuation greatly enhancing India’s Fintech ecosystem. KredX for instance is said to have generated US$ 23 million in revenues as of 2024 and counts the likes of Sequoia and Tiger Global as investors. Credable on the other hand has been able to raise over US$ 66m from investors and Veefin, an SCF platform IPO’d in 2023 and currently has a valuation of US$ 134 million. India’s SCF market is robust but most importantly, its growing. The key themes that have emerged from India’s success are digitisation and the growing role of non-banks in supporting SCF.

This matters because like Africa, India has had a history of working capital being financed by banks on the basis of tangible collateral. The growth of SCF is critical because its unlocking value trapped in Indian Supply Chains and enabling growth. It offers a roadmap, but can Africa chart a similar or better course?

Why Does This Matter

India and Africa have lots of similarities. For one, the idea of India as a homogenous blob suffers from the same pitfalls as thinking of Africa as a singular entity. Nonetheless, most Indians I’ve spoken to who do business in the continent always say how X is Y years behind India in terms of Z. Fill in the blanks as per whichever sector you’re in. Anecdotally this can be seen in the ease with which Indian Fintech concepts translate into the continent particularly in the banking sector. A few examples may suffice that aim to show the similarities;

A Growing Indigenous Industrial Base - Both India and Africa share colonial legacies particularly in their manufacturing and trading sectors. Immediately after independence, India and Africa both had manufacturing sectors dominated by European firms such as Unilever. Of course there have been local conglomerates for years as is the case with Tata in India and Dangote in Nigeria. However, from the 60s to the 80s, foreign firms dominated the commanding heights of the economy. Over time, local giants have emerged driven by entrepreneurs who have a better understanding of their economies and can better navigate the ever changing political tides. In Africa, the growth of companies like Mombasa Cement, Tolaram Group and of course the modern reincarnation of the Dangote Group stand out. Traditionally, SCF programs have relied on supporting foreign MNCs thanks to their “better” credit ratings. In India as in Africa, the market is shifting to support these local giants and their supply chains. It’s a competitive imperative given that its slowly becoming the only game in town;

Banks in both markets are not fully structured to support MSME’s. In India, there is a dual economy just like in most African countries. There is a structured formal economy that is mostly urban in nature serving formal sector workers and registered businesses. There’s also an informal segment that serves the majority of the population. Given this informality and when you consider factors such as GDP per capita and the sheer size of the country then banking SMEs becomes difficult. This is largely due to;

Cost to serve;

Collateral requirements given the high perceived risk;

Lack of formal records and a comprehensive history of credit scoring particularly for SME;s

Both India and Africa have a shared history of “leapfrogging” in certain domains. In the Telecoms industry, both experienced a telecom revolution where mobile telephony leapfrogged traditional landlines. In India, UPI has enabled a new type of financial inclusion that has Fintechs leading the charge. In Africa, Mobile Money and Mobile Based Fintech solutions have driven a new type of financial inclusion away from banks. Similarly, both can build an SCF industry on the back of Fintechs rather than banks.

Whereas Africa stopped at Mobile Money, India continued leveraging technology across a number of problem areas, SME credit being one of them. This is a journey that Africa should also embark on.

What Drove India’s SCF Success?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Frontier Fintech Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.