#24 What does the Future of Mobile Money Hold

A deep dive on how mobile money grew, it's key value proposition and some of the considerations around its future form

Hi all - This is the 24th edition of Frontier Fintech. A big thanks to my regular readers and subscribers. To those who are yet to subscribe, hit the subscribe button below and share with your colleagues and friends. 🚀

Warning - this week’s post is a bit long 🙈, but the topic deserves a bit of consideration. I analyse how Mobile Money started with M-Pesa, detail its core commercial value drivers and evaluate some of the challenges it faces in the new world.

Introduction

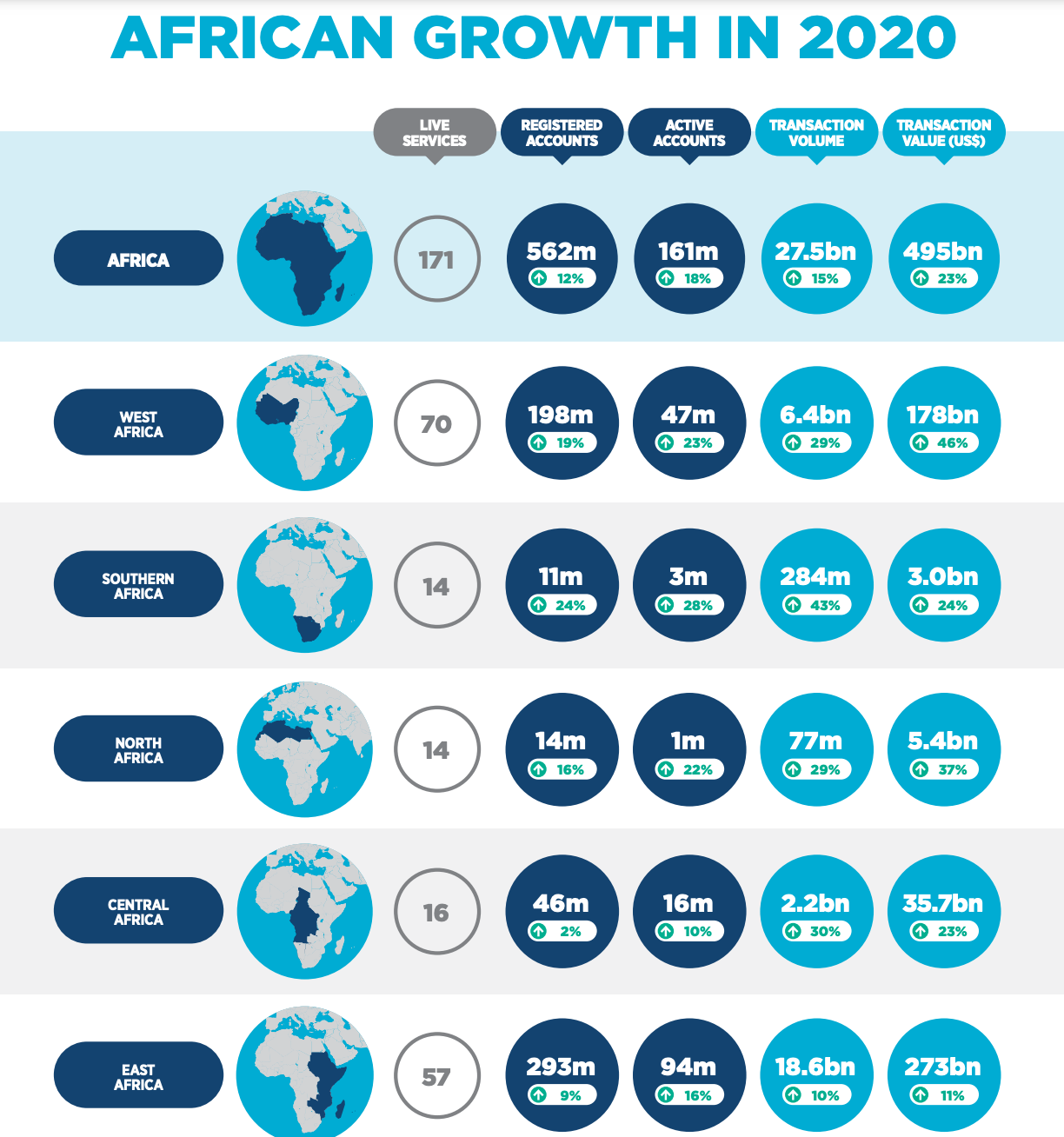

It has been 14 years since Mobile Money was introduced with the commencement of M-Pesa’s operations in Kenya in 2007. In that time, the growth has been phenomenal. As of the latest GSMA report, there are now 1.2 billion registered mobile money customers globally with over US$ 2 billion processed daily in transactional volume. The infographic below from GSMA captures the state of the global industry. In Africa, there are over 548 million registered accounts with transactional volumes of over US$ 490 billion per annum.

Source: GSMA State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money 2021

Source: GSMA State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money 2021

Of interest to me in this article is how we got here and what the future holds for mobile money operators. The current economic and industrial landscape as regards technology, commerce and talent are completely different to those that existed when Mobile money launched and scaled. How mobile money operators adjust and compete will be critical to their continued growth, success or even survival. I don’t have a crystal ball, I wish I did, but I will try to map out specific scenarios.

How it all started

Many tales have been told about the origins of M-Pesa, but I had the privilege to get the real account from someone who was involved from day one. The story begins in rural Kenya, particularly the Eastern province of Kenya. This was the early 2000s when the Kenyan economy was very vibrant and everyone was keen on accelerating the growth of the country. A lot of the help was channeled through Micro-Finance. Nonetheless, it was noted that for a specific MFI that was operating then, default rates were over 60%. Most beneficiaries of the loans were just not paying. The UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) was on the ground, participating in this lending project. Their studies showed that the real reason loan beneficiaries were defaulting was that the cost of making the loan repayments in terms of cost to travel to the MFI exceeded the repayment amounts given that these were micro-loans.

Safaricom was roped in to try and find a solution given that people were transferring value through airtime. It stood to logic that people could use this same system to transfer money to each other and to institutions. A lot of ideation followed thereafter and banks were roped in, but as usual, most of them turned their backs on this “crazy project”. I’m told of a meeting at the Norfolk Hotel in which most bank CEOs were invited to participate in this project, but by lunchtime most had left because I assume they had better things to do. The only bank that was keen ended up doing very well from this partnership.

DFID proceeded to fund the development of the system and this was hosted in Germany. The idea was simple: to deal with cash in cash out (CICO), Safaricom would recruit agents across the country who would be incentivised by CICO commissions. Since this was digital money, it would be critical that funds are held at a regulated commercial bank to ensure that the electronic money that resides in the mobile money system is matched by deposits in the banking system. The mobile money system would reside within the core telecom network and embedded into each sim-card so that it would be ubiquitous. After getting a letter of no-objection from the Central Bank, M-Pesa commenced operations and as they say, the rest is history.

Following on, plenty of iterations have been made. These have ranged from commercial adjustments with the introduction of super-agents in 2009 to technical changes including upgrades of the core platform, re-shoring to Nairobi and introducing the Daraja API.

How it Works

When you peer under the hood to understand the mobile money business model, it becomes apparent that it’s a genius innovation that is quite simple but powerful. This is particularly the case when you think about the idea behind Stablecoins. Stablecoins are digital currencies that are matched by real world assets such as cash and gold. Electronic money like that which is used in MoMo is essentially a stablecoin. Nonetheless, this is not the only innovation. Mobile Money, particularly M-Pesa, is an innovation stack, a powerful chain-link in which each element in the link adds value to the other elements.

Technical Architecture

I don’t have the technical expertise to accurately describe the technical architecture behind mobile money. Nonetheless, this article by Wiza Jalakasi is a good start so is this thread by Michael Kimani.

Essentially, the mobile money system is tightly packed into the sim-card. It thus rides on the whole telco infrastructure from base stations all the way back into the core network. Telcos reach out to vendors such as Comviva and Huawei to build the Mobile Money system. This is then embedded into the core network and rides on either STK or USSD as the customer user interface. The genius behind this is that the telco already has you as their customer and thus onboarding for mobile money doesn’t require any additional identity verification. This of course is dependent on regulatory edicts.

Thus MoMo is a fully integrated network where the telco owns the full stack from the sim-card to the base stations to the core network.

Commercial Structure;

Mobile Money runs on agent networks which are decentralised cash networks that enable clients to deposit and withdraw money from their mobile wallets. Cash accounts for over 95% of all transactions in Africa and thus these agent networks are critical. The genius is that the system can hold significant volumes of cash but given that there are multiple small agents, then system wide cash handling costs are minimal or non-existent. This is different from banks which incur significant cash handling costs to serve customers through branches and ATMs.

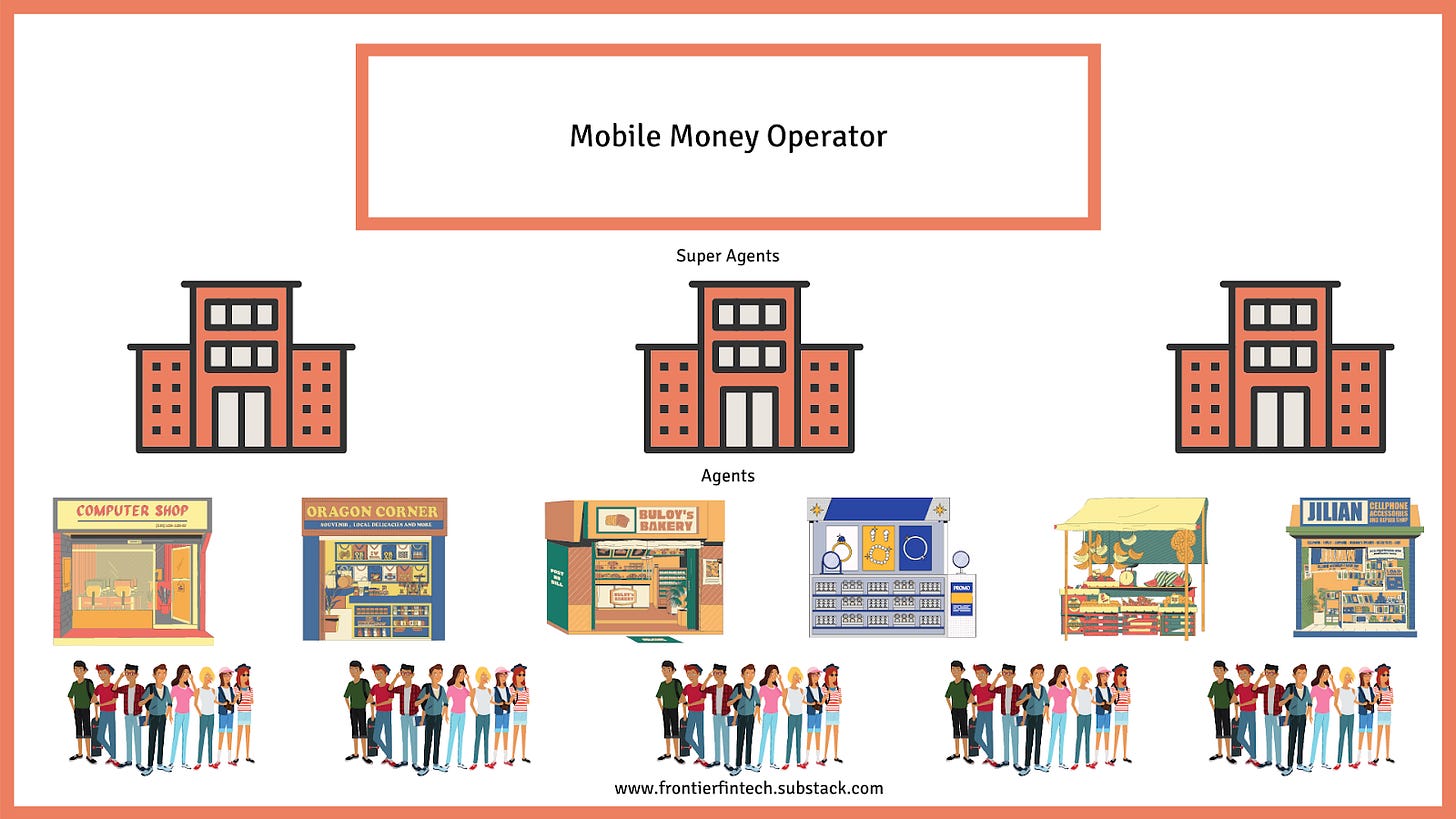

The diagram above shows the distribution structure of mobile money in most deployments. MoMo operators recruit super-agents who are charged with recruitment and float management for their agents. Agents on the other hand are charged with customer recruitment and cash in cash out operations for customers. The tariff structure has the following principles;

Cash-in tariffs are an expense to the Telco and are shared between the agent and the super-agent often on an 80:20 ratio. These differ depending on the telco and the market;

Cash out tariffs are shared among the agent, super-agent and the telco. Often on a 60:20:20 ratio with the agent getting 60%. The idea behind this is that revenues from cash out operations to the telco are used to cover cash in tariffs ideally with a margin.

P2P revenues accrue solely to the telco. However this is dependent on the telco issuing a strict edict against “direct cash-in”. Essentially, you can only deposit into your own wallet. This is enforced because if you could deposit into another wallet, the telco would incur the cost of that deposit whilst not benefitting from the P2P revenue. The whole model would collapse. I have seen markets where some telcos allowed direct cash-ins as a competitive move, but the whole market suffers. KYC is also a consideration here.

All other revenue lines such as B2C, C2B, C2G and others are pure revenue drivers for the telco with some cases of commission sharing where a third party vendor is selling through MoMo;

The agent network and the management of the same is a critical element of the business. Telcos were best placed to expand CICO agent networks because these are essentially FMCG distribution frameworks. These skills and capabilities already existed within the telcos due to their efforts to distribute sim cards across the country. I learned whilst building out a bank agent network that FMCG capabilities are a key differentiator and one needs to learn terms such as PiCOS (Picture of Success) at the point of sale, RED (Right Execution Daily) for sales routes and sales staff as well as SFE (Sales Force Efficiency). Banks typically don’t have these skills and often they are a cultural mismatch with the more staid elements of banking.

Summing it all up;

The above elements all work together to enable mobile money. A mobile money system often supplied by players such as Comviva and Huawei. A trust account maintained at a commercial bank, physical cash-in cash out agents grown and managed on FMCG principles and a traditional core network of sim-cards, base stations and core telecom systems.

In the case of Safaricom, it is arguable that the seeds for M-Pesa’s success started a long time ago. Innovations in the market such as per-second billing and their brilliant life-time commission sim-card sales strategy ensured market dominance prior to the launch of M-Pesa. The lifetime commission strategy was that; instead of a commission upon the sale of each sim-card, distributors were incentivised by getting a share of the commission whenever a sim-card was topped up with airtime. Distributors thus started giving out Safaricom sim cards for free knowing that they will recoup their cash on the lifetime airtime commission. When M-Pesa was launched, it was originally seen as a value added service to the core telecom business and a driver of customer loyalty. However the opposite dynamic was also at play, given that everyone was originally a customer of Safaricom, then moving to another mobile money player didn’t make sense. Mobile money works best if the telecom is already dominant in the traditional telecom business. This has been the case with Ecocash in Zimbabwe as well where Econet has a 78% market share.

Safaricom thus created a positive loop or fly-wheel where increased dominance in the telecom business drove increased growth in mobile money and vice versa.

Other deployments include;

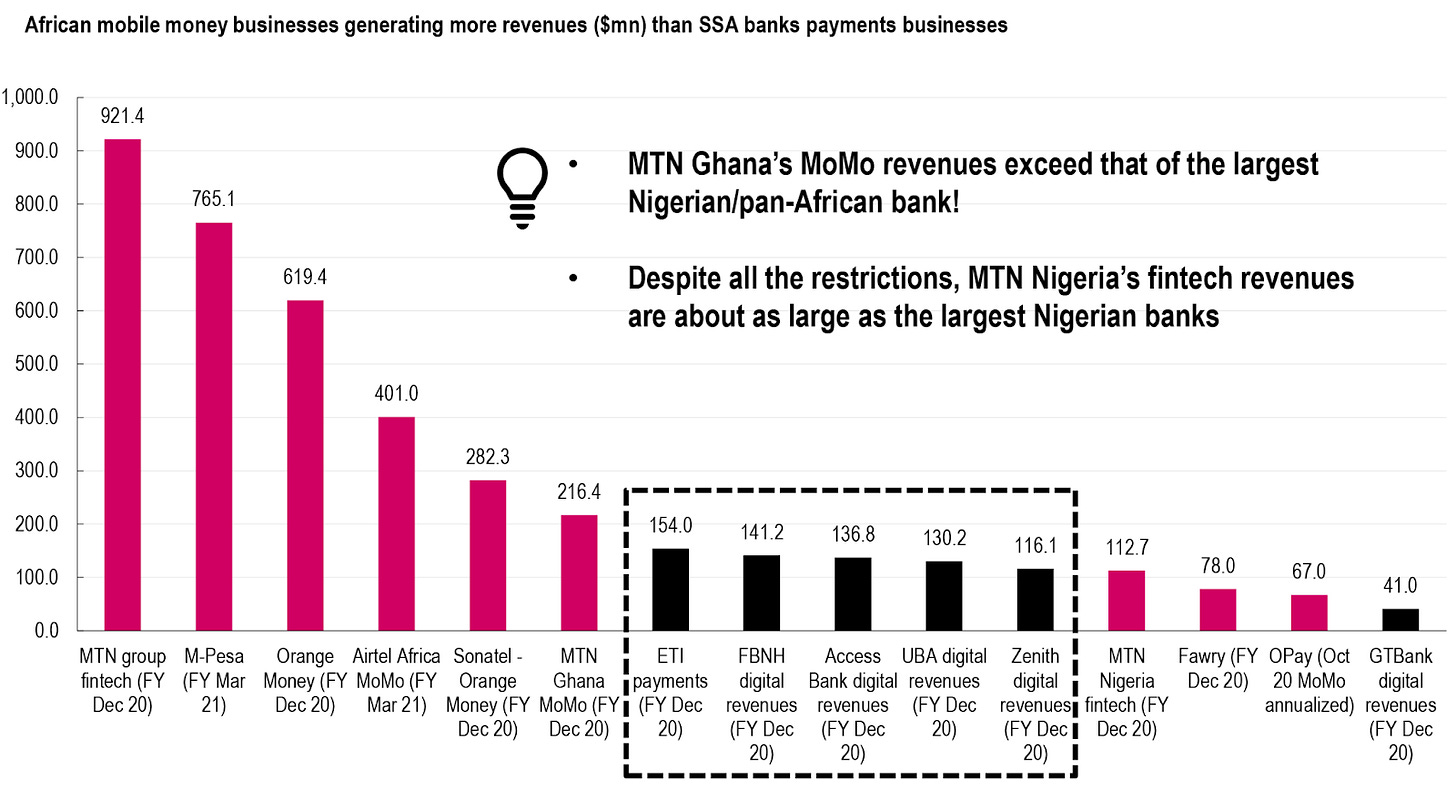

MTN’s Africa Mobile money operations which have total revenues of US$ 1.1 billion;

Airtel money’s African operations with total revenues of US$ 410 million;

M-Pesa Tanzania which accounts for the bulk of Vodacom’s Tanzania’s revenues with total revenues of US$ 154 million dollars;

Ecocash Zimbabwe which has total revenues of US$ 42 million;

M-Pesa had annual revenues of US$ 780 million;

The diagram below from the Africa Can blog gives a quite useful breakdown of MoMo revenues.

My view is that mobile money when implemented properly and supported by favourable regulation is significantly more powerful than any bank-led initiative. This is food for thought for Nigerian fintechs which are arguably riding on regulatory arbitrage by offering a mobile money like product whilst operating on a micro-finance or banking license. When regulatory approaches towards mobile money change, MoMo will thrive in Nigeria. It’s just a much better product when it comes to fulfilling its use case.

So what does the Future Look Like;

As we look into the future, different scenarios could emerge. MoMo operators are moving towards a super-app strategy, new digital banks and fintechs are emerging with unique customer propositions and regulation, technology and increased smartphone penetration are changing the market.

The Threat for Neobanks and Digital Payment Providers

Players such as Kuda Bank in Nigeria, Zazu from Zambia and Tyme Bank in South Africa are challenger banks that are mobile-first. Tyme Bank takes this further with Tyme Bank kiosks spread across retail malls in South Africa. In addition to these digital banks, phone manufacturers such as Transsion, the manufacturer of Tecno, Infinix and Itel brands are looking to play in this space. Transsion have launched PalmPay in Ghana and Nigeria. A recent report by BCG showed that only 13 out of 249 global Digital Challenger deployments are profitable. Of these, some of the successful DCB’s only account for 2% of total assets within the market. The diagram below from Wiza Jalakasi’s blog post is very useful;

These players are riding on themes such as increasing internet and smartphone penetration. My view is that these players may do well in markets which don’t have a dominant mobile money player such as Nigeria, South Africa and Zambia. The main issue is the cash in cash out infrastructure which is required for cash heavy markets. Tyme Bank is attempting this with their kiosks which so far seem to be doing well. Building CICO infrastructure is expensive and suffers from a chicken and egg problem. You need customers to attract agents and you need agents to attract customers. Down the line, open banking and instant payment systems may create the UPI-like conditions that enable multi-bank agency banking to thrive. Nonetheless, regulations will have to change. For instance, in Kenya, a bank has to pay KES 1,000 (US$ 9) per agent despite the fact that this agent has already been reviewed and vetted by the CBK. For OEM’s, O-Pay’s experience in Kenya shows that it’s not easy to dethrone a full-stack solution like M-Pesa;

The Super-App Opportunity

Recently, Vodacom has announced a partnership with Alipay to launch a Super-App in South Africa. Safaricom’s M-Pesa recently unveiled their new app which is intended to be a super-app. MTN is also working towards a super-app. The super-app strategy is inspired by the Eastern success of apps such as Wechat, Alipay, Grab and Gojek. The idea is to be the central app from which clients can access all their lifestyle requirements.

The original success of Mobile Money rode on existing capabilities within the telco as I’ve detailed before. A lot of the resource capabilities existed within the market particularly as regards I.T maintenance and FMCG. FMCG skills are a dime a dozen in Africa due to the presence of companies such as Coca Cola, Unilever, Diageo and British American Tobacco. The concern is whether the skills required to build a world class super-app are present in the markets at a sufficient scale. These skills range from product management to deep AI capabilities. Vodacom has partnered with Alipay with the view to close this skills gap through the partnership. Nonetheless, the question that emerges is how much value Alipay will extract from this relationship and whether Vodacom will have any intrinsic competitive advantage. Another issue that emerges is whether for the bulk of Africans who live day to day, lifestyle apps are a core value proposition.

In terms of organisational design and structure, the super-app strategy can be viewed to be tenuous. To attract world class talent, pay and reporting structures will need to change. Top engineering talent is expensive particularly in Africa and the question is how will these firms legislate for a junior engineer earning way more than a senior manager in sales and distribution. The lack of success from previous initiatives such as Bonga a messaging app, Masoko an e-commerce website and Sasai by Cassava Fintech can be traced to industry 3.0 thinking with an industry 4.0 product. Nonetheless, the new crop of leadership within these organisations are cognisant of this. The new Safaricom CEO for instance has cleverly stated that he wants to transform Safaricom to be a technology company. This is brilliant and timely as it means significant internal restructuring.

Rails on Rails on Rails

The MoMo stack has the potential to be disintermediated and MoMos need to be cognisant of how they will play going forward. The idea behind this is that MoMo players should decide what their true north star is. Visa is a great example. It defines itself as a global payments technology company that connects consumers, businesses and governments in over 200 countries. Their stated mission is;

“Our mission is to connect the world through the most innovative, reliable and secure payments network — enabling individuals, businesses and economies to thrive.”

With this mission, Visa has invested in Tink and had a previous failed investment in Plaid. Additionally, Visa is enabling crypto payments and settlements. The idea is that if your goal is to connect the world through payments, then you have to constantly evolve as payment methods change.

The MoMo stack is under-attack, from a UX perspective, different players are coming with more intuitive user experiences for customers. With regards to payments and settlements, new and emerging challenges such as open banking and instant payment systems are emerging. Tanzania, South Africa and Kenya all have payment strategies that envision instant payments modelled on UPI of India. Ghana and Nigeria already have live Instant Payment systems. Open API’s also challenge the idea of agent networks. It’s possible with current technology to enable self-onboarding of agents on apps with digital KYC and anti-fraud technology.

MoMo in Africa could define their mission similarly to Visa as to enable payments across the continent by connecting people, businesses and governments. This could lead to interesting pivots such as acquiring switching companies. Airtel have hived off their Mobile Money business at a valuation of US$ 2.75 billion. MTN have suggested that they plan to do the same with their fintech business having a valuation of between US$ 5 and 6 billion. These new entities could then have the operational and strategic independence to pursue visa-like business models. The idea is that if you focus on the rails, then you can build a continental giant that handles most of the payments within the continent. The interesting thing here is that since Telcos will deploy 5G, Mobile Money could be the payments layer for IoT, particularly payments by things such as robots and cars.

The future is indeed interesting and it would be fun to watch. What’s sure is that when the underlying competitive framework changes, then failure to evolve can be fatal. We have witnessed this with computing in the 80s when companies like Cisco took advantage of distributed networking.

As always thanks for reading and drop the comments below and let’s drive this conversation.

If you want a more detailed conversation on the above, kindly get in touch on samora.kariuki@gmail.com;

Hi Samora, I really like how the article discusses the future of mobile money. It's well-structured and insightful. I believe the next big opportunity for mobile network operators is to offer financial services as value-added services. They can achieve this by forming strong partnerships to enable payments across different channels like POS and ATMs, and by integrating seamlessly with banks. This could lead to significant advancements in the mobile money industry.