#18 Considerations on Global Payments, Remittances and the Tech around this;

Thoughts around cross-border payments and how they will evolve;

Hi all - This is the 18th edition of Frontier Fintech. A big thanks to my regular readers and subscribers. To those who are yet to subscribe, hit the subscribe button below and share with your colleagues and friends. 🚀

Executive Summary

Cross border payments are a US$ 150 trillion per year business generating revenues of over US$ 200 billion. Remittances to Lower Middle Income Countries (LMICs) are just shy of US$ 600 billion with 10% of this going to Africa. Traditionally payments were made through SWIFT and the corresponding banking network that was built to enable settlements.

SWIFT emerged out of improvements in communications technology that happened in the 1960s and the push towards creating SWIFT was the standardisation of messages. Prior to SWIFT, banks used to exchange messages through free form Telex communication. Starting with a few banks, SWIFT has grown to over 11,000 members and processing over 42m transactions per day. Nonetheless, SWIFT is not the intuitive payments system of our time particularly for small C2B, C2C and B2B payments.

Companies such as Wise are emerging which can be loosely defined as digital Hawala systems. These companies are expanding their product offering to business accounts and payments as a service propositions. The question is where do African Fintechs and Banks play in this sector.

In Africa, issues such as low intra-African trade, multitudes of currencies, capital controls and restrictive trade and labour movement policies have hindered intra-African payments. Nonetheless these are changing. Banks need to adopt to offer more payment options in addition to SWIFT and Fintechs need to work on creating interoperability infrastructure.

Introduction

This week I would like to discuss a topic that is gaining a lot of attention recently and in which most of us have encountered, often in a negative light. The issue of cross-border payments and remittances. Particularly, some of the major themes that are emerging within this space from a Fintech perspective and how I see them evolving in the near term. Of course, as with all Frontier Fintech newsletters, historical context is always given.

Cross-border payment volumes and the statistics around these are complex and one needs to be careful with the numbers. Remittances are much easier to understand. Remittances are often defined as consumer to consumer transfers of money across borders often by diaspora workers. Cross border payments encapsulate a wider subset of payments that include C2B, B2C and B2B payments for trade, commerce, investments and consumption.

Total remittance volumes to Lower Middle Income Countries (LMICs) are estimated to be around US$590 billion as per World Bank statistics. The long-term growth rate is expected to be 4%. Cross-Border payments on the other hand are estimated to grow to over US$ 156 trillion by 2022. McKinsey estimates that revenues from cross-border payments are roughly US$ 200 billion. This figure consists of trade finance fees, FX margins and transaction fees. The diagram below offers a good breakdown of total international payment revenues.

Source: McKinsey

The bulk of cross-border payments revenues come from B2B payments with trade finance and FX fees accounting for 56% of total revenues.

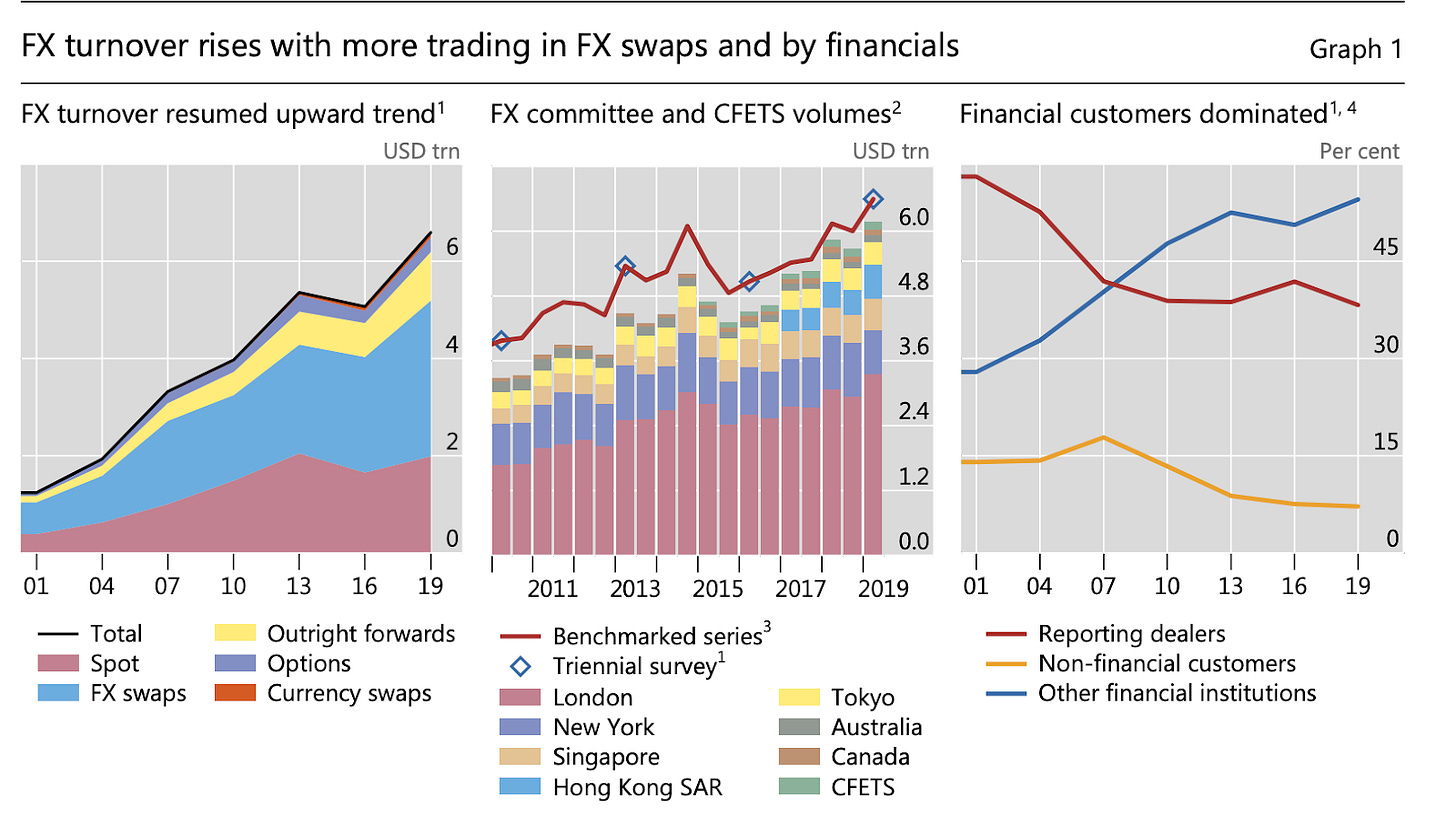

These figures are not to be conflated with global FX volumes which according to the Bank of International Settlements were roughly US$ 6 trillion per day or US$ 2.1 quadrillion per annum. FX volumes nowadays consist largely of financial transactions based on hedging and speculative purposes with trade accounting for only 8% of total FX volumes.

Source: Bank of International Settlements

Therefore the figures we’re interested in are cross-border payment volumes and remittances. Within Sub-Saharan Africa, total remittances are roughly US$ 60 billion with Nigeria accounting for a third of remittances followed by Ghana and Kenya. I like to focus on total cross-border payments largely because the narrative changes from Africa being a recipient continent to a narrative that Africa wants to take part in the modern global economy. Additionally, remittances are a sub-set of cross border payments.

Cross Border payments were traditionally handled through correspondent banking relationships with communications and standardisation occurring through SWIFT.

The diagram above shows the typical cross-border payments structure.

History of International Payments - From Telegrams to Telex to SWIFT

In a previous post, I detailed how Western Union and Wells Fargo transitioned from courier services to financial service players. A similar history emerges with American Express. The underlying point was that payments at core is about communications and how changes in communication technology impacts payments. Additionally, communication service providers have an advantage when it comes to enabling payments. It is no surprise that M-Pesa emerged from Safaricom which is a communications company. Additionally, M-Pesa disrupted the post-office and bus couriers which were the main form of transferring money in Kenya.

Therefore, to analyse the future of cross-border payments, one has to review the evolution of our current cross-border architecture with SWIFT at the core.

The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) is a membership of over 11,000 banks. SWIFT is responsible for providing the platform, products and services that allow member institutions to connect and exchange financial information - the secure exchange of proprietary data. SWIFT is concerned with the secure exchange of payments information and does not involve itself in settlements. The settlements leg of cross-border payments is handled via Correspondent Banks.

Prior to SWIFT, banks used Telex technology to exchange communications. The advances in Telex from Telegram technology was driven by improvements in message routing, switched-network technology and the typewriter keyboard. The Telex enabled truly global communications between banks with most parts of the world having a Telex machine. Nonetheless, the issue with Telex machines was that they were based on free-form text i.e. operators would write financial instructions in “free-form” english. This led to significant operational errors when it came to executing transactions.

Around this time i.e. the 1960s, improvements in technology laid the foundations for globalisation and large global banks chased their customers globally. Banks such as Citibank, Bank of America, Barclays and Midland Bank in London expanded their global operations. The demand for secure, reliable communication channels grew significantly. Moreover, communication systems that relied on public networks such as the Telex used volume driven rates which would be expensive for banks particularly as payments volumes increased.

Citibank’s IT Centre in New York developed a proprietary system called MARTI (Machine Readable Telegraphic Input) and pushed it to other banks for adoption. Nonetheless, other banks balked at Citi’s attempt to impose an industry standard upon them. This should always serve as a warning to banks attempting to impose infrastructure on others. The continual duplication of efforts drove increased frustration amongst banks and drove the realisation that they needed to cooperate to define common standards for secure message exchange.

In the late 60s and early 70s, the Societe Financiere Europeene, a consortium of six major banks based in Luxembourg and Paris initiated a message switching project. By 1971 over 68 financial institutions based in 11 countries both in Western Europe and the USA had enough interest to set up a feasibility study to examine the possibility of setting up a private international communication network. This finally led to the formation of SWIFT in May 1973 as a non-profit cooperative based in Brussels. At its founding, SWIFT was formed of 239 banks from 15 countries. This has grown to over 11,000 members globally. In 1979, SWIFT was processing over 120,000 messages per day; currently SWIFT processes over 42million messages per day.

Tying this all together is a network of correspondent banks that handle settlements based on the SWIFT messages. There are hundreds of SWIFT message types usually classified as MT XXX with the XXX being a three digit number that references the type of transaction. MT stands for message type. So for example, MT 103 stands for a simple single customer credit funds transfer and MT 320 confirms the terms for fixed/term loan/deposit transaction.

To transfer money from say Nigeria to China, you have to go to your bank which has to be a SWIFT member. The bank will ask for beneficiary details which must include the beneficiary bank SWIFT address. The bank will then send a SWIFT message to the correspondent bank in the form of an MT 103 requesting the bank to execute the transfer on its behalf. The network of correspondent banks are often European or American banks. Thus the SWIFT communication and settlements will occur between Nigeria and USA with the final payment being sent to China. This complex web of correspondents and communications leads to slow payments, high costs and often a lack of traceability of the payments. SWIFT has tried to fix this with SWIFTgpi nonetheless not all member banks have upgraded to SWIFTgpi.

The diagram above gives a high-level summary with the dollar sign referencing charges.

A number of issues arise from this correspondent framework, particularly with reference to Africa that are causing Fintechs to innovate within this space;

Naturally, SWIFT was formed in the 1970s based on the technology of the time. As the internet and the API economy have emerged, then SWIFT is not the intuitive money movement architecture needed in the 21st century;

The multitude of counterparties needed to execute a payment leads to higher fees with bank to bank cross-border C2C payments costs of over 10%;

Global correspondent banks have pulled back from Sub-Saharan Africa making it more difficult for smaller countries to take part in the global economy. Burundi and Zimbabwe are prime examples;

There is no link between the flow of payments vis-a-vis the flow of trade. According to SWIFT, 20% of commercial payments within Africa are destined to other African countries meanwhile only 11% of payment flows are to Africa. Additionally, North America and Europe account for 70% of payment flows despite accounting for only 40% of trade flows.

A new discussion about cross-border payments is emerging with players such as Wise (formerly Transferwise), CurrencyCloud and World Remit and away from SWIFT and traditional players such as MoneyGram and Western Union. All the same, the latter two are making significant investments in technology.

Disrupting Cross-Border Payments - A Wise Case Study;

Wise formerly Transferwise is one of the companies seeking to disrupt cross Border payments. The company was founded in 2011 after its founders Kristo Kaarman and Taavet Hinrikus faced frustrations whilst sending money between Estonia and London. Taavet was one of the founders of Skype and thus had first hand experience in how technology can be used to disrupt an incumbent industry - in this case global telephony. The issue they had was that at the time, Taavet was based in London but got paid in Euros whereas Kristo worked at Deloitte, got paid in pounds but had a Mortgage in Estonia. Transferring money from London to Estonia was expensive with the banks making most of their money from opaque FX commissions. Their initial solution was to make transfers between each other. Kristo would exchange his pounds for Euros to pay his mortgage and Taavet would exchange his Euros for pounds with Taavet.

They then formed Transferwise back in 2011 as a tech-first way to make cross-border payments by cutting out the middleman i.e. the SWIFT and correspondent networks. Initially, Wise was structured for peer to peer markets, particularly Euro-Pound and Euro-Dollar transactions. Nonetheless the business model evolved to a situation where Wise opened accounts in multiple institutions and would settle directly from its accounts. The video below gives a good breakdown of how they manage global settlements;

Wise has gone on to achieve a number of milestones and pivots. Wise is a member of Faster Payments UK and SEPA thus enabling low cost direct to account transfers. Additionally, Wise has launched borderless business banking capabilities offering multi-currency accounts, invoicing payments through integrations with the likes of Xero and payroll capabilities. This from a customer perspective looks like any other Neobank such as Revolut. Interestingly, average balances per account for Wise work out to GBP 2k per customer compared to GBP 250 for Revolut. In addition, Wise has launched Wise as a Service capabilities by integrating to banks and recently Temenos so as to enable other financial service providers to ride on their technology.

Currently Wise moves around US$ 72 billion per year with around 25% of these being business payments. Most of their business clients have 50 employees or less signifying their dependence on SMEs. Most of their business payments are in the tens and hundreds of thousands mark with regards to single payments.

Wise is currently profitable with a net profit of GBP 20.4 million on revenues of GBP 302.6 million. Their gross margin works out to roughly 67% calculated as bank and FX costs as a percentage of total costs. The bulk of Wise costs are employee expenses, consultancy costs and outsourced services. Wise has thus managed to scale their overall transactional volumes in a profitable manner whilst maintaining profitability.

It can somehow be thought of as a tech-enabled Hawala system but with the capability to enter different verticals. Some of the tailwinds supporting the Wise business model are;

Integrations to global instant payment services. One can foresee a world where every country has an instant payment service such as Faster Payments and UPI, Wise can integrate all these and enable real-time global funds transfers;

Increasing e-commerce and e-service provision through platforms such as Upwork will drive demand for global cross-border payments that are efficient;

The growth of Direct to Consumer propositions like Shein and Pinduoduo are significant factors to consider. Trade was often driven by wholesalers buying from manufacturers and breaking bulk in retail. These commercial relationships were naturally correspondent bank based with LC’s and guarantees underpinning them. Direct to consumer envisages a move from trade to commerce thus C2B payments.

Of course being tech-first in the 21st century is critical and will enable Wise to move faster than incumbents.

Considerations for Africa

Within this context i.e. moving away from a correspondent bank framework to digital cross-border payments, shifts in economic structure and improvements in technology; How should African Fintechs and Banks play in this sector.

First, some considerations that help to understand Africa better;

Intra-Africa trade works out to around 16% of total trade compared to intra-EU trade at 65% and ASEAN trade at 45% this definitely affects the volume of cross-border payments;

Given that most African countries are commodity based, capital controls are often used to mitigate the impact of shifts in commodity prices. Capital controls are a drag on money movement. Remittance inflows are encouraged but outflows are discouraged;

Intra-Africa migration is growing. According to IOM over 21 million African nationals were living in a neighbouring country in 2019 up from 18.5 million in 2015. Most international migration occurs within the continent. One obviously has to adjust for refugee movements, but within Africa its clear that more migration is happening;

Increased infrastructure investments. Africa has legacy colonial infrastructure that was designed to take commodities out and import consumer goods. This infrastructure wasn’t designed for intra-african trade. Governments are changing this with their infrastructure investments. Additionally AfCTFA should be a boon to trade;

Multiple currencies and disjointed regional settlement systems. There are over 50 currencies in Africa and over 5 regional settlement systems often using US$ as their settlement currencies.

All these factors i.e. capital controls, multiple currencies and asymmetric capital flows create the perfect conditions for Hawala type “off-line” systems rather than official digital channels. An example is the ubiquity of M-Pesa agents in countries in East Africa. These agents outside of Kenya act as foreign exchange bureaus and mobile money agents and operate under the radar.

Having set the scene of increasing trade and migration, and of course a growing remittance base. How should banks and Fintechs evaluate all this?

Building local global remittance firms could be a risky business. Ultimately source markets include North America, Europe, Middle East and parts of Asia. Players such as Wise, World Remit and Paypal are present in these markets. These companies are well-funded and some such as Wise are perpetually looking for ways to lower costs and integrate into more partners such as Mobile Money. I don’t see any significant competitive advantage accruing to a local player based on costs, brand or efficiency. If anything, a customer facing remittance app will have significant CACs whilst operating in a very competitive market;

The likes of Wise and Western Union are directly integrating to banks and thus the play seems to be shifting from having the C2C customer interface to just providing the technology;

Payments infrastructure seems an interesting space. MFS in Africa is a growing player with a business model that’s based on interoperability of Mobile Money. The business is based on netting out positions on a monthly basis and faces the issue of capital controls and asymmetrical payment flows. Despite this, one can argue that interoperability is partly solved; the current phase of interoperability is based on making payments across borders using your mobile phone. The next phase should include transacting across borders. For instance, an M-Pesa user should be able to transact on M-Pesa at a Uganda MTN mobile merchant - This is the magic of Visa. The opportunity is thus based on creating a multi-tenant agency banking and merchant acceptance system. A regional bank is well placed to execute this.

Banks should consider their global payments infrastructure, organisational design and customer propositions. The idea should be to integrate the likes of Wise, Western Union and Terrapay onto their payments engine. When a customer wants to make a cross-border payment, the payments engine should naturally route it based on consumer preferences such as costs and speed. As it is, most banks default to SWIFT for even small payments.SWIFT should only remain for large corporate customers. Wise is making moves by integrating both to banks and to Core Banking providers such as Temenos;

Players such as Eversend and Chipper Cash are trying to solve for inter-African money movement. Their journeys are similar to those of Wise - from an initial idea of P2P cross-border payments, they are evolving to offer their services as APIs and offering Neobank like store of value propositions;

Embracing modern tech whilst accounting for local nuances should unlock a lot of value in the African cross-border payments space. It will be interesting to watch how this space evolves.

As always thanks for reading and drop the comments below and let’s drive this conversation.

If you want a more detailed conversation on the above, kindly get in touch on samora.kariuki@gmail.com;